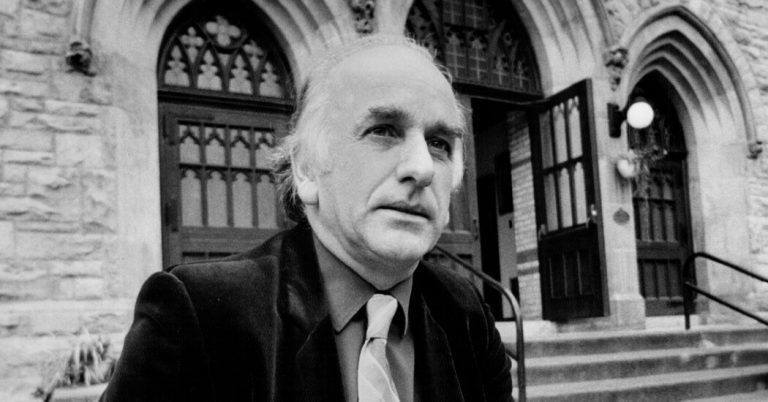

Derek Humphry, a British journalist whose experience helping his late wife end her life led him to become a crusader in the right-wing movement and publish “Final Exit”, a best-selling guide to suicide, has died. died Jan. 2 in Eugene, Ore. He was 94 years old.

His death, in a hospital unit, was announced by his family.

With a populist flair and a knack for talking the mean about death, Mr. Humphry almost single-handedly galvanized a national debate about physician-assisted suicide in the early 1980s, a time when the idea was little more than an inside theory struck by medical ethicists.

“He was the one who really put this cause on the map in America,” said Ian Dowbiggin, a professor at Prince Edward University and the author of “A Concise History of Euthanasia: Life, Death, God and Medicine” (2005). “People who support the concept of assisted suicide owe the doctor absolutely a big thank you.”

In 1975, Mr. Humphry worked as a reporter for the Sunday Times of London when Jean Humphry, his wife of 22 years, was in the final stages of terminal bone cancer. Hoping to avoid prolonged suffering, she asked him to help her die.

Mr. Humphry procured a lethal dose of painkillers from a sympathetic doctor and mixed them with coffee in his favorite mug.

“I took the mug from her and told her if she drank it she would die instantly,” said Mr. Humphry in the Daily Record in Scotland. “Then I gave her a hug, a kiss and we said our goodbyes.”

Mr. Humphry characterized the emotional, taboo and legally-violating pursuit of his wife’s death in “Jean’s Way” (1979). The book, the excerpt in newspapers around the world, was a sensation. Readers sent letters to the editor discussing the plight of their loved ones. Many wrote directly to Mr. Humphrey.

“I wish we had a solution like yours,” wrote one woman, describing the last eight weeks of her husband’s life as “horror.” “How much more beautiful, how much more ‘love.’ We did what others forced us to do and experience this terrifying ‘death’ that the medical world gives by prolonging life in every possible way.’

In their letters, some readers asked for guidance on helping their loved ones die. This prompted Mr. Humphry, by then remarried and working in California for the Los Angeles Times, considered creating an organization to advocate for assisted suicide and end-of-life rights for the terminally ill.

Ann Wickett Humphry, his second wife, suggested using Hemlock as a title, “arguing that most Americans associate the word with the death of Socrates, a man who deliberated and planned his own death,” Mr. Humphry in an updated version of “The Way of Jean.”

In August 1980, they rented out the Los Angeles Press Club to announce the founding of the Hemlock Society, which they ran out of the garage of their Santa Monica home.

The organization grew rapidly. In 1981, he published “Let Me Die Before I Wake,” a guide to drugs and dosages to induce “peaceful self-confidence.” The group also lobbied state legislatures to enact laws making assisted suicide legal. In 1990, the Hemlock Society moved to Eugene. By then, it had more than 30,000 members, but the right-to-fly conversation had yet to reach most dinner tables in America.

This changed dramatically in 1991, after Mr. Humphry published “Final Exit: The Practices of Assertiveness and Assisted Dying”. The book was a 192-page step-by-step guide which, in addition to explaining suicide methods, provided Miss Manners-like advice for getting out of grace.

“If you are unfortunately forced to end your life in a hospital or motel,” he wrote, “it is polite to leave a note apologizing for the shock and inconvenience to the staff. I have also heard of one person leaving a generous tip in a motel staff.”

The book quickly shot to #1 in the Hardcover Advice category of the New York Times Best Sellers list.

“This is an indication of how big the issue of euthanasia is in our society now,” bioethicist Dr. Arthur Caplan told The Times in 1991. “It’s scary and disturbing, and this kind of sales is a shot across the bow. It’s the most powerful statement of protest of the way medicine deals with terminal illness and death.”

Reactions to the “final exit” were generally divided along ideological lines. Conservatives dropped it.

“What can one say about this new ‘book’?” In a word: evil,” University of Chicago bioethicist Leon R. Kass wrote in Commentary magazine, calling Mr. Humphry “The Lord High Executioner.” “I didn’t want to read it, I don’t want you to read it. It should never have been written and is not worth capitalizing on a review, let alone an article. “

But progressives embraced the book, even as public health experts expressed concern that the methods outlined could be used by depressed people who were not terminally ill.

“I’ve read ‘Final Exit’ out of curiosity, but I’ll keep it for another reason — because I can imagine, having once nursed a cancer patient, the day I’d want to use it,” The New York Times columnist Anna Quindlen wrote, adding: “And if that day comes, whose business is it, really, but mine and that of those I love?”

Rather than worry about the book’s contents, Ms Quindlen said: “We need to look at ways to ensure that death with dignity is available in places other than the chain bookstore in the mall.”

Derek John Humphry was born on April 29, 1930 in Bath, England. His father, Royston Martin Humphry, was a traveling salesman. His mother, Bettine (Duggan) Humphry, was a fashion model before she married.

After leaving school at the age of 15, Derek took a job as a newspaper messenger. The following year, the Wistol Evening World hired him as a journalist. He went on to report for the Manchester Evening News and the Daily Mail before moving to the Sunday Times of London and then the Los Angeles Times.

Before you turn to books about death, Mr. Humphry wrote Because He’s Black (1971), an examination of racial discrimination written with Gus John, a black social worker. and “Police and Blacks” (1972), about racism and corruption in Scottish shipyards.

Mr. Humphry was a polarizing figure even within the right-wing movement.

In 1990, he and Mrs. Wickett Humphry divorced and fought bitterly in the media. She called him a “fraud”, accusing him of leaving her because she was diagnosed with cancer. Mr. Humphry denied the allegation.

“This has been a very crazy marriage,” she told The New York Times in 1990. “This is extremely painful, as bad as Jean’s death. I’ve lost my house. I’ve been living in a motel for three months.”

Ms. Wickett Humphry killed in October 1991.

In a video recorded the day before, she expressed doubts about the work they had done together, including helping her parents end their lives at home.

“I ran away from home thinking we’re both murderers,” he said in the video, which was reviewed by the Times.

Mr. Humphry went into “Damage Control” mode, he told the Times. He placed a half-page ad in the paper explaining his side of the story.

“Unfortunately, for much of her life, Ann was fraught with emotional problems,” the ad said, adding that “suicide due to depression was never part of Hemlock’s faith.”

Mrs. Wickett Humphry’s death and misgivings about the right move put a strain on Hemlock society. Mr. Humphry stepped down as Executive Director in 1992 and started the euthanasia research and advocacy organization.

The Hemlock society eventually split into several new groups, including the final exit network, which Mr. Humphry helped start it.

He married Gretchen Crocker in 1991. She survives him, along with three sons from his first marriage. three grandchildren. and a great-grandson.

Lowrey Brown, a Final Exit Network “Exit Guide” who helps terminally ill patients plan their deaths, said in an interview that her clients sometimes credit Mr. Humphry and the “final exit” to give them the courage to end their lives.

“It was the Hemlock Society and the book ‘Final Exodus’ that really crossed the threshold to get this into ordinary living rooms of Americans as a topic of discussion,” said Ms. Brown. “You could talk about the Thanksgiving table.”

If you are having suicidal thoughts, call or text 988 to reach Suicide and Life Crisis or go Speessallyofsuicide.com/resources for a list of additional resources.