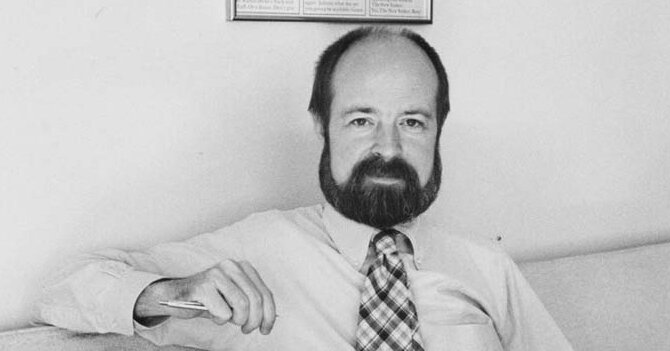

William Whitworth, who wrote revealing profiles in The New Yorker giving voice to its idiosyncratic subjects and handled the prose of some of the nation’s best-known writers as an associate editor before transplanting that magazine’s arduous standards to The Atlantic, where he was editor-in-chief for 20, died Friday in Conway, Ark., near Little Rock. It was 87.

His daughter, Kathryn Whitworth Stewart, announced the death. He said he was being treated after several falls and operations at a hospital.

As a young college graduate, Mr. Whitworth abandoned a promising career as a jazz trumpeter to pursue a different kind of improvisation as a journalist.

He covered breaking news for The Arkansas Gazette and later The New York Herald Tribune, where his colleagues eventually included some of the most exciting voices in American journalism, including Dick Schaap, Jimmy Breslin and Tom Wolfe.

In 1966, William Shawn, the suave but dictatorial editor of The New Yorker, charmed Mr. Whitworth into the beloved weekly. He took the job even though he had already accepted one at the New York Times.

At The New Yorker, he inspired wit in thoughtful “Talk of the Town” vignettes. He also profiled the famous and not-so-famous, including jazz greats Dizzy Gillespie and Charles Mingus (accompanied by photos from former Herald Tribune colleague Jill Krementz) and foreign policy adviser Eugene V. Rostow. He expanded his profile of Mr. Rostow in a 1970 book, “Naïve Questions About War and Peace.”

Mr. Whitworth offered each person he described ample opportunities for reference, providing each with equally abundant gems to pick up.

In 1966, with characteristic detachment, he wrote about Bishop Homer A. Tomlinson, a gentle man from Queens who ran a small advertising agency and now, presiding over a Church of God flock, had proclaimed himself King of the World. Bishop Tomlinson asked millions of colleagues — including all Pentecostals. “He thinks they are his,” wrote Mr. Whitworth, “whether they know it or not.

Of Joe Franklin, the perennial TV and radio host, Mr. Whitworth wrote in 1971 that his office, ”if he were a person, he’d be a bum” — but that ”on the air, Joe is more cheerful and positive than Norman Vincent Peale and Lawrence Welk together.

From 1973 to 1980 at The New Yorker, then at the venerable Atlantic Monthly, where he was a contributing editor until his retirement in 1999, and later, when he worked on books, Mr. Whitworth was most appreciated as a nonfiction editor.

Apart from the writers he shepherded, encouraged and protected, his role was largely unheralded outside the publishing industry. To colleagues who often wondered why he left reporting, he suggested that he couldn’t lick them, so he joined later: He was simply fed up with publishers, especially newspaper editors, messing with his prose, which would nevertheless be published under the by line.

“You want to fail on your own terms, not in someone else’s voice that sounds like you,” he told the Oxford Aspiring Writers of America Summit in 2011.

Mr. Whitworth edited such relentless perfectionists as the film critic Pauline Kael (who almost got into a fight with Mr. Shawn) and Robert A. Caro (who was ultimately so satisfied with the final excerpts from “The Power Broker,” his biography of Robert Moses, published in The New Yorker — after Mr. Whitworth mediated with Mr. Shawn — that when The Atlantic published a condensation of the first volume of his biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, he asked Mr. .Whitworth to edit it).

How did he win over unruly writers?

“As long as you kept them in the game and didn’t do things behind their backs, slowly explaining why this would help them, something that would help them, protect them not us, and they came around,” he told the Oxford Americas Summit .

For Mr. Whitworth, said the essayist Anne Fadiman, who worked with him at The American Scholar after he left The Atlantic, “editing was a conversation and also a form of teaching.”

Sometimes Mr. Whitworth offered sage advice that went beyond editing.

After Garrison Keillor wrote an article for The New Yorker about the Grand Ole Opry, “it prompted me to do an Opry-themed Saturday night variety show myself, which led to ‘A Prairie Home Companion,'” it gave me work for years to come,” Mr. Keillor said by email. “Unusual. Like a sportswriter who becomes a major league player, or an obit writer who opens a morgue. I’ve been grateful ever since.”

The New Yorker writer Hendrik Hertzberg wrote on his blog in 2011 that despite Mr. Whitworth’s capacity for self-deprecation, he and Mr. Shawn had much in common, “including a genial manner, an acute understanding of writerly nerves and of a deep love. of jazz.”

In 1980, Mr. Whitworth was considered the most likely candidate to succeed Mr. Shawn, who was stubbornly unwilling to succeed him. Instead of being complicit in what he described to a friend as “manslaughter” in a plot to oust Mr. Sean, he accepted the editorship of The Atlantic from its new owner, Mortimer Zuckerman. He had no regrets.

“I passed The New Yorker a long time ago.” she wrote in a letter to Corby Coomer, former editor and food columnist at The Atlantic — which she said “fulfilled all my expectations and hopes.”

“I couldn’t be as happy and proud in any other job,” he added.

Under Mr. Whitworth’s editorship, The Atlantic won nine National Magazine Awards, including the 1993 Citation for Overall Excellence.

He also worked for months editing the copy for Renée C. Fox’s In the Field: A Sociologist’s Journey (2011) in a correspondence that went on for months without ever meeting face-to-face.

Mr. Whitworth’s sentences, Professor Fox recalled in Commentary in 2011, “were usually written in his characteristically apt style, always polite, gentlemanly, and modest in tone, sometimes self-deprecating and often dryly witty.”

“The editor,” she continued, “taught the writer about intellectual, grammatical, aesthetic, historical, and ethical elements of writing and editing that were subtle or unknown to her before.”

William Alvin Whitworth was born on February 13, 1937, in Hot Springs, Ark. His mother, Lois (McNabb) Whitworth, was a china and silver buyer at Cave’s Jewelers (where she often helped Bill Clinton buy gifts for Hillary). His father, William C. Whitworth, was an advertising executive.

He attended Central High School while working part-time as a copywriter in the advertising department of The Arkansas Democrat. After graduation, he majored in English and philosophy at the University of Oklahoma, but dropped out before the end of the year to play trumpet with a six-piece jazz band.

He married Carolyn Hubbard. died in 2005. In addition to their daughter, he is survived by a half-brother, F. Brooks Whitworth. A son, Matthew, died in 2022. Mr. Whitworth had lived in Conway since retiring from The Atlantic.

The literary agent Lynn Nesbitt remembered Mr Whitworth as a “stunningly brilliant and demanding editor” whose “own ego never got in the way of his publishing brilliance”. Charles McGrath, another former New Yorker editor who later edited the New York Times Book Review, said that Mr. Whitworth, unlike Mr. Sean, “was more loved than feared.”

But he was not repulsed. While he often quoted Mr. Shawn as saying that “lacking perfection is just an endless process,” he more or less replicates what he called the New Yorker’s “neurotic system” of meticulous editing in The Atlantic.

“He taught me that the worst approach for an editor is to get your feet wet on a piece because you knew how to organize and write it better,” said Mr. Kummer, who is now executive director of Food & Society in Aspen Institute. .

“The writer’s name was on the piece, not yours,” he continued, “and no matter how heated the disagreements over phrasing, punctuation, paragraph order, or word choice, the writer had to be happy with a piece. , otherwise it shouldn’t be running. .”

When he commissioned Mr. Kummer to edit an article by George F. Kennan, the distinguished diplomat and historian, Mr. Whitworth warned Mr. Kummer in no uncertain terms: ”As much work as you think it takes, remember: He’s a giant. “

But when Mr. Kennan later complained that Mr. Kummer “got me into as much trouble as The New Yorker,” Mr. Whitworth replied, “That’s exactly what I’m paying him to do.”