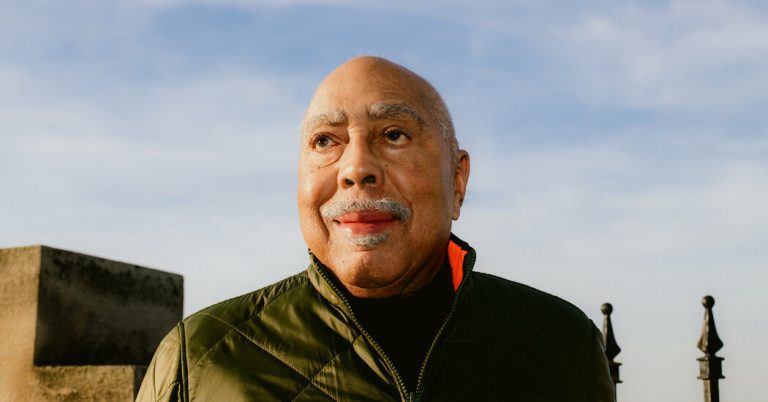

And unlike pop-culture depictions of theoretical physicists — scribbled lonely on blackboards, shrouded in clouds of chalk dust — Dr. Massey likes to work with people. In turn, people think of him so much that he says his name in the right rooms. He completes one project and soon another one falls into his lap. He also tends to inherit organizations in need of some direction – most recently Giant Magellan, which is facing financial turmoil.

The involvement of Dr. Massey’s work on the telescope came toward the end of a presidency at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. During a board meeting for the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts, Robert Zimmer, then president of the University of Chicago, approached him about serving on the board of Giant Magellan. A year later, Dr. Massey was elected president.

But among all his positions and accolades, one stands out, Dr. Massey said. In 1995, he assumed the presidency of his alma mater, Morehouse College, a historically black men’s college in Atlanta and the site of Dr. King’s funeral. “Without Morehouse,” he said, “I just wouldn’t be who I am.”

Torn between worlds

Dr. Massey grew up in Hattiesburg, Miss., at the height of segregation. If you were Black, he remembers, you sat in the balcony at the movies, rode buses in the back and slipped through the side entrances of stores — if you could shop there. And when a white man was on the sidewalk, you got out of the way.

Desperate to leave, he was thrilled when, at 16, he won a scholarship to attend Morehouse. But he quickly realized that his classmates looked down on people from Mississippi. “And so I said, ‘I’ll show them,'” Dr. Massey said. “What is the hardest lesson?” He chose physics because he felt he had something to prove.

In a consortium of four colleges, he was the only student in the year studying physics. But he was never alone. Instead, he liked to get lost in the equations. Years later, in his memoirs, Dr. Massey described a “total absorption that is as close to a meditative state as I have ever achieved.”

This passion led him to a doctoral program at Washington University in St. Louis, where he studied how liquid helium behaved near absolute zero. In 1966, he earned his Ph.D., joining a group of more than a dozen black physicists across the nation who had accomplished the same feat.

Soon after, Dr. Massey moved to Chicago to work at the nearby Argonne National Laboratory, studying the strange behavior of sound waves in the superfluid sun, which seemed to defy the laws of physics. His work caught the attention of Urbana-Champaign researchers as well as Anthony Leggett, a theorist at the University of Sussex in England, whose understanding of helium would later win him the Nobel Prize in Physics.