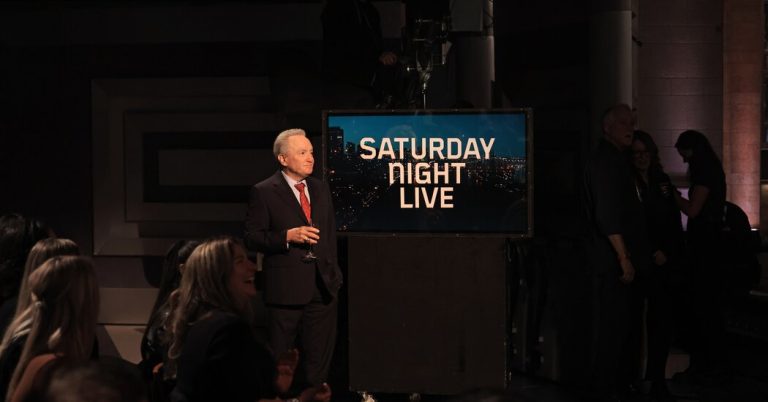

It’s 1:01 a.m. on a Sunday morning in May, and Lorne Michaels, the creator and producer of “Saturday Night Live,” has just finished the final episode of the 49th season. He spent those 90 minutes walking backstage, hands in pockets, surveying the actors, allowing himself only an occasional chuckle of satisfaction.

As cast members flood the stage to celebrate another year in the books, they enthusiastically embrace each other and the evening’s host, actor Jake Gyllenhaal, and musical guest, pop phenomenon Sabrina Carpenter.

But on the floor, Michaels, 79, just finished his 20th show of the year with resignation: “I only see mistakes,” he says. Some jokes could have landed better, and he second guesses his choice to shorten some sketches. He’s likely to spend the weekend going over every detail, he says. By Monday, he’ll find some measure of satisfaction – until he has to do it again.

Michaels, through “SNL,” has built an entertainment empire that has survived for half a century despite the demise of traditional television.

He hates to call himself a CEO, but beneath his Canadian humility he’s become something of a management guru: He spends his days recruiting top talent, managing egos, meeting near-impossible weekly deadlines, wading into controversy — skillfully, in most cases — and navigating a media landscape that has put many of its peers out of business.

All this time, unlike most CEOs who have become the face of their brand, he has studiously avoided the limelight.

“I’ve spent my life next to things to be more in the shadows,” Michaels said, describing what management professors might call a servant leadership style. “You’re supposed to make other people look good.”

Recruiting may be Michaels’ superpower. He has found comedy talent across generations: Dan Aykroyd, Chevy Chase, Eddie Murphy, Will Ferrell and Tina Fey.

“Primarily, you’re looking for whatever that spark is that says it’s original,” Michaels said. “It’s just an instinct that the way their mind works, something more interesting will happen.”

Part of his approach is to look beyond the usual suspects, hotshot comedians in Los Angeles and New York, and instead try to find new talent in the middle of America.

It’s gotten tougher since the pandemic destroyed many of the live venues that served as farm groups for the “SNL” stars. Second City, which spawned Gilda Radner, John Belushi, Chris Farley and Fey, faced additional pressure over its handling of the race and was sold to private equity firm ZMC in 2021, reportedly for $50 million.

Last season, Michaels leaned more heavily on celebrity hosts such as Kristen Wiig, a former “SNL” exec, to ease the pressure on his less experienced cast, he said.

Michaels is well aware of the challenges new stars face. “If you were the funniest kid in your class or school, and then you work professionally and everyone else in the room is,” he said. “It can be annoying or it can be really stimulating.”

Once these talents reach their peak, Michaels’ job often gets harder, not easier. Hand holding takes a different shape.

“No one can handle fame,” Michaels said. “Generally, we’re more tolerant of it, but you know people are going to be jerks. Because it’s just part of that process, because nobody grew up like that.”

Some in his cast have handled the spotlight more easily than others. Both Belushi and Farley died of drug overdoses at the age of 33 after their appearances on the show. Pete Davidson, who left “SNL” in 2022, has openly discussed his anxiety and time in rehab.

It’s partly Michaels’ calmness, suggested Paul McCartney, a longtime friend, that makes the weekly comedy circus that is “SNL” possible.

“He’s a benevolent dictator,” said McCartney, who first met Michaels at a party McCartney threw at Harold Lloyd’s Greenacres estate in Beverly Hills, California. to instill in everyone a sense that this is going to work.”

In a sea of chaos, Michaels reigns over “SNL” with practiced discipline. He has never missed a Saturday night and arrived at a table read soon after the birth of one of his three children. There is a weekly routine, including a Monday meeting at 6 p.m. during which Michaels introduces the host and Tuesday night at an Italian restaurant.

“The idea that on Friday night we still don’t have an opening is no longer scary,” he said. “It’s not common, but it’s not unusual.”

The show often stirs up controversy, but it can also deal with it by accident, turning Michaels into a crisis manager, as when musician guest Sinead O’Connor tore up a photo of Pope John Paul II in 1992.

“SNL” dropped comedian Shane Gillis in 2019 after racial slurs he made on a podcast came to light. Gillis is now selling out stadiums and the show brought him back this year as host.

“I think ideas thrive in an instant,” Michaels said of the quick reaction and seemingly equally quick forgiveness. “They used to call them rages.”

Those who have hosted the show, and Michaels, say its intensity and longevity have created a culture uniquely suited to staging it: Makeup artists transformed an actor into Butt-Head (Beavis’ partner) in three minutes. Costume designers created a quick replica of all the clothes from Prince Harry’s wedding. The writers grew up watching and now serve as a sounding board for Michaels, who started out as a writer himself.

“He’s listening — he’s having a dialogue with all these people about what’s funny, what’s working,” said actress Emma Stone, a five-time host. “There is like a cerebral trust where he cultivates.”

Unlike most businesses, when things go well at SNL, the best people leave. Wiig, Ferrell, Maya Rudolph and more have gone on to have huge film and television careers.

“I met Lorne in ’91 or ’90,” said Chris Rock, whose career went on to include several movies with his “SNL” co-star Adam Sandler. “I’ve never been broke since.”

Instead of getting upset when talent leaves and the challenge that turnover creates, Michaels seems to embrace it as part of the model. He says he offers the same advice to all the big names who come sit on his couch and tell him they’re planning to leave: “Build a bridge to the next thing, and when it’s solid enough, cross over. But don’t leave the first thing, because you don’t know what’s really out there.”

Sometimes, even when stars cross the bridge, they stay in Michaels’ orbit. His media company, Broadway Video, produced “30 Rock,” “Mean Girls” and “Wayne’s World.” He tapped Jimmy Fallon from the cast of “SNL” to host “The Tonight Show,” which is also produced by Broadway Video, along with the rest of NBC’s late-night lineup.

Michaels’ broader remit also requires dealing with the industry’s tough finances. Recently, NBCUniversal cut Seth Meyers’ late night band amid broader industry budget cuts.

“I think everybody had to go through some belt-tightening,” Michaels said of the cuts. “I think the only person who really believes in the network model right now is Ted Sarandos, who seems to be building one,” he added, referring to the Netflix co-CEO.

NBC has seemingly granted “SNL” unusual independence. (The 46th season cost about $138 million to produce, according to public records.) That’s likely because, in addition to serving as NBC’s talent factory, “SNL” helps the network stay in the cultural conversation.

The show’s 50th season will look to celebrate its influence on media and pop culture. Music producer Mark Ronson and Michaels will, in effect, make a homecoming at Radio City Music Hall on February 14th. There will also be a prime-time special featuring current and former stars that Sunday. Questlove, the musician and producer, is co-producing an anniversary documentary about “SNL’s” mark on music and culture, and Morgan Neville is producing five documentaries about “SNL” and Michaels.

The celebration will inevitably raise questions about Michaels’ retirement. The show mocked the age of both presidential candidates: Donald Trump, 78, and Joseph R. Biden, 81. But as Michaels prepares to lead off a landmark season, industry insiders have wondered if he’s preparing for his own. SNL Dispatch. And they are already starting to speculate who would take his place.

Michaels deflects the question, shifting the spotlight from him to the show: “I’ll do it as long as I feel like I can do it,” he said. “But I rely on other people and always have.”

Thanks for reading! I’ll see you on Monday.

We’d love your feedback. Send your thoughts and suggestions to dealbook@nytimes.com.