L. Clifford Davis, a lawyer for civil rights who led to attempts to distant Gymnasiums in Texas, sometimes in view of the violence of mobs, hostility from government politicians and threats in his life, died on February 15 at Fort Worth. It was 100.

Karen Davis’ daughter confirmed death in a nursing facility.

Although the US Supreme Court ruled out the separation of the public school in 1954 in its ruling in Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka – a case in which Mr Davis had worked with Thurgood Marshall in his early stages – many cities and states across the south initially defied the decision.

He was left to lawyers like Mr Davis to hold these local areas to be held accountable. Started with the Texas Mansfield. The city’s only high school was only white and black students had to find their own way in a black high school, traveling 20 miles to Fort Worth.

On behalf of the five students, Mr Davis sued the Mansfield school district in 1955 and a year later a Federal Court of Appeal decided in favor of them.

But when black students arrived for the first day of school in September 1956, they met hundreds of angry white people, some holding nooses. The combustion crosses were on the screen.

Mr Davis appealed to US Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. for help, but refused. Mr Davis then wrote to Governor Allan Shivers in Texas.

“These Negro students exercise a constitutional right,” Mr Davis wrote. “I invite you as a ruler to challenge additional law enforcement officers to Mansfield to assure that law and order will be maintained.”

Shivers governor developed Texas Rangers – but just to keep peace. He made it clear that he would do nothing to impose the decision of completion.

At one point, a friend of Mr. Davis offered him a weapon for protection, warning him of white Vigilantes. He took the gun but never used it. However, he received threats of death in the post office, though he got up.

As tensions increased, Mr Davis decided that the risk for the students was too high and pulled his efforts to bus them in white schools.

But continued to push the cause. In 1959, he brought a charge against the Fort Worth school system, which remained separated. He won and this time the system agreed to a plan to integrate his schools.

Such a work, later reflected, was the epitome of what lawyers should seek.

“The philosophy that turned to us at that time was that lawyers were social engineers,” he said in an interview with 2014 for the University of North Texas. “It was our job to try to use the principles of law to help equality and the opportunity for all people, not just black people.”

L. Clifford Davis (the original L. did not support a name) was born on October 12, 1924 in Wilton, in southwestern Arkansas, where his parents, Augustus and Dora (Duckett) Davis were Sharecripers.

Wilton was deeply separated and the local black school system stopped in the eighth grade. Clifford’s parents hired a house in Little Rock, the state capital, where they lived with five of his six brothers while attending high school and college.

He graduated from Philander Smith University (now Philander Smith University), a historical black institution, in 1945 with a degree in Business Administration.

Mr Davis wanted to go to the Law School, but there was no one in Arkansas who would receive black applicants, so he moved to Washington, DC, to attend Howard University.

Finding the cost of life in Washington, however, felt that time was mature to try to distance the Law School at the University of Arkansas, applied for entry there in 1947.

The school, at Fayetteville, offered him a point, but with a great warning: he would have no contact with white students and had to pay his tuition tuition in advance.

Mr Davis refused and remained at Howard, graduated in 1949, but his efforts did not go to waste. In 1948, Silas Hunt, taking the same offer, became the first black student at Arkansas Law School.

Mr Davis initially practiced the law in Pine Bluff, south of Little Rock. He moved to Texas in 1952, settled in Fort Worth, where he became the first black lawyer in the city to open a practice.

He worked with NAACP and other political rights groups, participating in the early stages of the case that became Brown V. Board of Education, led by Thurgood Marshall, the future associate of the Supreme Court of Justice.

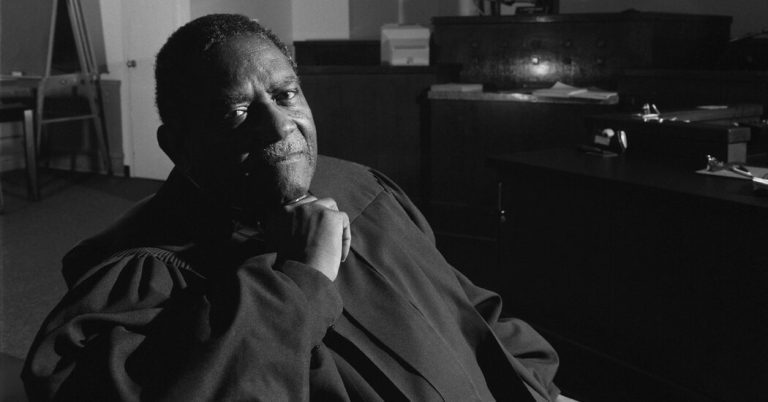

In 1983, Mr Davis was named a judge of the Criminal Court of Criminal Court and won the election the following year. He lost his re -election in 1988, but remained a judge visiting until he retired in 2004.

Together with Karen’s daughter, she survives another daughter, Avis Davis. His wife, Ethel (Weaver) Davis, died in 2015.

Judge Davis was not one to look for the spotlight, but over time he found him. In 2012, Fort Worth’s Black Bar Association, which helped be found in 1977, was renamed L. Clifford Davis Legal Association in his honor.

And in 2017, the Law School of the University of Arkansas gave him an honorary degree.

“He never crossed my mind that this would happen,” he told Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. “I put 71 years ago to win a degree. Now they will give me one.”