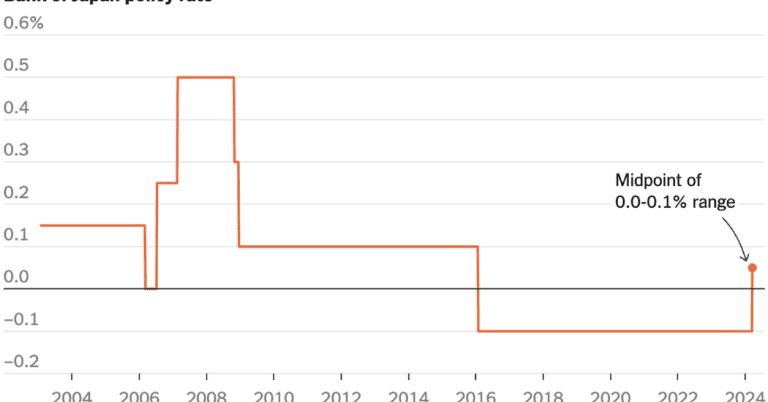

Japan’s central bank raised interest rates for the first time since 2007 on Tuesday, pushing them above zero to close a chapter in its aggressive bid to stimulate an economy that has long struggled to grow.

In 2016, the Bank of Japan took the unorthodox step of cutting borrowing costs below zero, in an effort to jump-start lending and borrowing and boost the country’s stagnant economy. Negative interest rates – which central banks in some European economies have also implemented – mean depositors pay to leave their money in a bank, an incentive to spend it instead.

But Japan’s economy has recently begun to show signs of stronger growth: inflation, after being low for years, has accelerated, boosted by larger-than-usual wage increases. Both are signs that the economy may be on a path to more sustainable growth, allowing the central bank to tighten interest-rate policy years after other major central banks quickly raised interest rates in response to a jump in inflation.

Even after Tuesday’s move, interest rates in Japan are far behind those of the world’s other major developed economies. The Bank of Japan’s policy rate target rose to a range of zero to 0.1 percent from minus 0.1 percent.

The bank, in a statement on Tuesday, said it had concluded the economy was in a “virtuous circle” between wages and prices, meaning wages were rising enough to cover rising prices but not so much as to limit business profits. Japan’s headline inflation measure was 2.2% in January, the most recent data available.

The central bank also scrapped policies in which it bought Japanese government bonds, as well as funds that invest in real estate or track stocks, to keep a lid on how high market interest rates can rise, encouraging businesses and households to they borrow cheaply. The bank slowly eased policy over the past year, leading to higher debt yields as the country’s growth outlook improved.

The bank said negative interest rates and other steps it had taken to stimulate the economy “have fulfilled their role”.

In many countries, rising inflation has tormented consumers and policymakers, but in Japan, which has more often experienced growth-sapping deflation, the recent rise in prices has been welcomed by most economists. Japan’s stock market, boosted by an upturn in the economy and shareholder-friendly corporate reforms, has attracted huge sums of money from investors around the world, recently helping the Nikkei 225 index break a record high it had held since 1989. The Nikkei rose 0.7 percent on Tuesday.

The move away from negative interest rates, which will help shore up the country’s weak currency, is seen by investors as another important step in Japan’s recovery.

“It’s another milestone in the normalization of monetary policy in Japan,” said Arnout van Rijn, a portfolio manager at Robeco, who founded and ran the Dutch fund manager’s Asia office for more than a decade. “As a long-term fan of Japan, this is very important.”

Interest rate hike bets were boosted this month after the Japan Confederation of Trade Unions, the country’s largest labor union, said its seven million members would receive wage increases averaging more than 5 percent this year, the biggest annual increase since negotiations since 1991 This added up to an average wage increase of about 3.6 percent in 2023.

Before the results of the wage negotiations were announced, investors expected the Bank of Japan to wait longer to raise interest rates.

“This decision was based on the belief that the Japanese economy itself is changing, rather than short-term concerns,” said Shigeto Nagai, head of Japanese economics at Oxford Economics.

Accelerating wage growth is a critical sign for policymakers that the economy is strong enough to generate some inflation and is able to withstand higher interest rates. Like other major central banks, the Bank of Japan targets annual inflation of 2 percent. the rate has been at or above that for nearly two years.

The rise in wages signals that companies and workers expect prices to remain higher, Mr van Rijn said. “People no longer believe that prices will fall enough to penetrate wage demands.”

The Bank of Japan, in its statement, concluded that “it is highly likely that wages will continue to rise steadily this year, following solid wage growth last year.”

Shizuka Nakamura, 32, a resident of Yokohama, a port city south of Tokyo, said she had noticed prices rising. “I feel the rising cost of living,” said Ms. Nakamura, who works in a management job at a construction company. She recently had a child.

“My friends who are around my age and who also have kids all say that things like diapers and baby formula are getting more expensive,” she said.

The Bank of Japan’s interest rate move was also significant because it was the last major central bank to leave negative interest rate policy. It and central banks in Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and the eurozone broke monetary policy taboos by pushing interest rates below zero – which essentially means depositors pay banks to hold their money and creditors they’re borrowing less money than they’re lending out – in an effort to spark economic growth after the 2008 financial crisis. (Sweden ended negative interest rates in 2019, and the other European central banks followed in 2022.)

Negative central bank policy rates have lifted global bond markets, with more than $18 trillion of negative-yielding debt trading at its peak in 2020. As inflation and economic growth have returned, central banks have also raised their policy rates – much more aggressively from Japan’s debt – almost no debt has a negative yield.

Rising interest rates in Japan make investing in the country relatively more rewarding for investors, but the Federal Reserve’s target rate is still about five percentage points higher and the European Central Bank’s is four points higher. While foreign investors have started pouring cash into the country, for Japanese investors overseas yields remain attractive, even as the Fed and ECB are expected to start cutting interest rates, preventing a rapid repatriation of cash to Japan.

The Bank of Japan also suggested it would make a gradual policy shift. Raising interest rates too quickly could kill growth before it is possible.