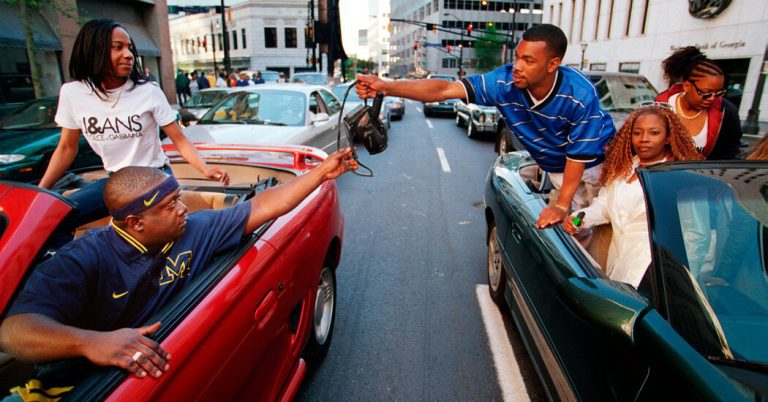

Back then, hundreds of thousands of young, mostly black students descended on Atlanta each spring for the rowdy and rowdy event called Freaknik. Artists such as Notorious BIG, OutKast and Uncle Luke performed across the city. The movement hardly moved at all, and why would it? The party was right there on the street.

Three decades have passed. Parties turned professional. Children were born. Wardrobes have evolved. All the while, some who were in the middle of it all were perfectly content knowing that their youthful exploits that might be a little embarrassing today were hidden. They had their memories. The photos were stacked in shoe boxes. As for what was caught on tape, who has video anymore?

But a new documentary threatens to shake things up.

“Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told” promises to be more than a racist exposé, exploring the transformation during the 1980s and ’90s of a modest cookout for students at the city’s historically Black colleges into a sprawling spectacle that consumed Atlanta.

Even so, for months, the conversation surrounding the documentary, which was released Thursday on Hulu, has included the curiosity and concern of attendees who are now in their 40s and 50s, wondering if they could appear in it. .

The concern led to threats of legal action. A bystander preemptively called for divine intervention. “I pray Jesus is a big, tall privacy fence,” she wrote on social media platform X.

In a nod to the concern, producers said the releases were signed by those who shared their footage and faces were blurred to protect identities in scenes that were more clear.

In any case, much of the discussion was good-natured and entertaining, with the feeling that what appears in the film is more likely to cause a chill than a scandal. However, it suddenly thrust members of the camcorder generation into a TikTok-era predicament.

“You don’t think, ‘Twenty, 30 years from now, somebody’s going to see me,'” said Rhonda Ratcha Penris, a cultural historian and author who participated in Freaknik twice in the 1990s.

That said, she and others argue that any discomfort is worth it if it means exploring the complexities of a rally often remembered in Atlanta for the disruption it caused and its ignominious demise. City officials cracked down on Freaknik, effectively killing him, before the 1996 Olympics. (Lesser variants using the Freaknik name continued.) In the mid-1990s, there were allegations of sexual assault, public drunkenness, and looting of during the one-day event.

“It was a headache for some, and I get that,” said DJ Mars, who played at Freaknik as a student at Clark Atlanta University before embarking on a career that included touring with Usher and other major artists. “As an adult, I see what the problem was.”

But for the young people immersed in it, the atmosphere was electric. Freaknik — a portmanteau of “freak” and “picnic” — has been described as a black alternative to both Woodstock and the spring break craze that swept Florida’s beaches.

“It was like a takeover, an epic takeover,” said Lori Hall, co-founder of a marketing agency who lived in Atlanta and started attending Freaknik festivities as a teenager. “We were living life and we felt like we had the power, the power to just be and that was a really cool thing about the culture.”

The event, especially at its peak, introduced the promise of Atlanta to a new generation. Many who came for a weekend ended up returning for good, including Tyler Perry, the media mogul who built one of the country’s largest movie studios on 330 acres in the city.

“While all the kids were numb, drinking and partying, I was waking up to possibility,” Mr. Perry, who grew up in New Orleans, wrote in his book, “Higher Is Waiting.” “I saw that there were black people who were doing great things in their lives. There were black doctors, lawyers, business owners,” he added. “I knew Atlanta was the place for me.”

For many, Freaknik represented more than a festival: It was an annual infusion of music, fashion and culture.

“It wasn’t the cell phone era,” said Ms. Penrice, who first watched Freaknik in 1994 while studying at Columbia University in New York. “There was no Internet. It was really word of mouth. It’s hard to explain how everyone knew, but everyone knew.”

The filmmakers have collected footage from those holding their camcorder tapes, using it to capture the energy that pulses through the event and the city. The documentary, which premiered at South by Southwest this month, has high-profile supporters. Jermaine Dupri, the rapper and producer, is an executive producer, as are rappers 21 Savage and Uncle Luke.

In a recent appearance on Tamron Hall’s daytime talk show, the host put the question directly to Uncle Luke: “Should people be afraid of this documentary on Freaknik?”

“Yes,” he said, laughing.

His response likely did little to quiet the debate that sprung up as soon as the film was announced and continued for months on social media, podcasts, YouTube videos and blogs.

“The ‘Freaknik Aunties’ are rocked,” reported Revolt, an outlet covering hip-hop culture. On butter.atl, a popular Instagram account in the city, comment threads on posts about the film included those with similar concerns or others who wanted to keep a close watch to see if they could spot people they knew.

“Me zooming around trying to find my husband in his prime,” wrote one person.

“Put the moms and grandmas on the streets,” wrote another.

And perhaps, most importantly: “Who delivered the video.”

Whether it was the filmmakers’ intention or not, the surprise produced a “dreamy marketing ploy,” said Miles Marshall Lewis, a pop culture critic and writer.

“Everyone who experienced Freaknik in real time will watch it at least once,” he added, “to be safe from the incriminating footage.”

Mr. Lewis first attended in 1989 as an 18-year-old student at Morris Brown College, one of the city’s historically black institutions, along with Spelman, Morehouse and Clark Atlanta.

“Everyone of a certain age attended at least once or knew someone who went,” he said, “and they came back with outrageous stories about what happened.”

DJ Mars wasn’t all that interested in which of those stories made it into the documentary. He wanted to hear the music. He wanted to see the fashion: the “Homey the Clown” T-shirts, the Nike Cortez sneakers, the African American College Alliance sweatshirts, the tennis skirts that weren’t complete without a pager clasp.

“It’s a flashback to my youth, basically,” he said.