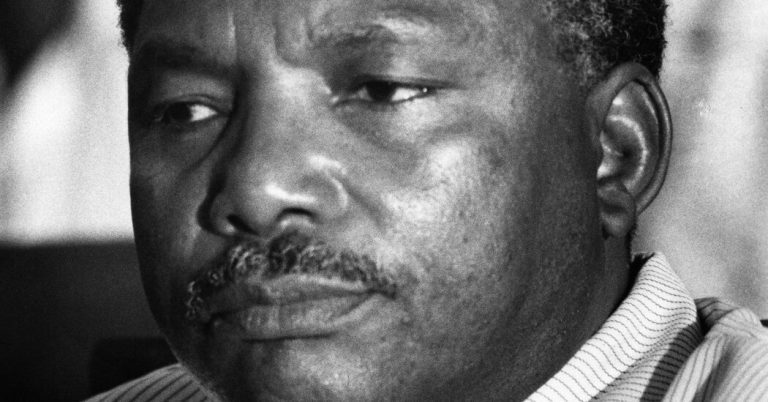

Ali Hassan Mwinyi, a teacher-turned-politician who led Tanzania as its second president after independence and helped dismantle the dogmatic socialism of his predecessor, Julius K. Nyerere, died on Thursday in Dar es Salaam, its former capital country. It was 98.

The current president of Tanzania, Samia Suluhu Hassan, announced the death, in hospital, on X, formerly known as Twitter. He said Mr Mwinyi had been treated for lung cancer.

Mr Mwinyi was 60 when he assumed the presidency in 1985 as the hand-picked successor to Mr Nyerere, who had volunteered to step down after ruling his country since its independent nationhood as Tanganyika in 1961 and its merger with Zanzibar in 1964 to create the state of Tanzania.

At the time, the peaceful transition was seen as a precedent in a continent that had developed a reputation for political violence as the main driver of change or succession.

But critics said Mr. Mwinyi, who went on to serve two five-year terms before stepping down in 1995, had little of the charisma and international stature of Mr. Nyerere, an African politician closely involved in struggles among independent nations for termination of the Portuguese and the Portuguese. British colonial influence in Mozambique, Angola and Zimbabwe and to support the enemies of apartheid in white-ruled South Africa.

Among Tanzanians, Mr Nyerere was known as Mwalimu — Kiswahili for teacher. Mr Mwinyi, by contrast, was nicknamed Mzee wa Rukhsa, which loosely translates as an elder who allows almost anything.

At the same time, however, Mr Nyerere’s socialist rule – based on the concepts of agrarian collectivisation, nationalization of industries and bureaucratic centralization – had led to economic failure, including shortages of foreign exchange and basic goods, heavy debt and dependence on foreign aid, much of it from the Nordic countries. Tanzania had also fought a devastating war with neighboring Uganda that toppled dictator Idi Amin but deepened its own economic decline.

Diplomats have described Mr Mwinyi as a timid compromise candidate, the victim of a predecessor who refused to relinquish the powerful post of party chairman at the same time he handed over the presidency. Indeed, Mr Nyerere told his successor that, having ruled for 24 years, he would continue to “whisper in his ear” to pass on his accumulated wisdom.

It was not until 1990 that Mr Mwinyi became the leader of Chama Cha Mapinduzi, the governing institution in his one-party state. In 1992, he oversaw a special congress that approved constitutional changes creating a multiparty political system.

Despite the official change, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, the Revolutionary Party, has remained the dominant political force for decades and the presidency has been occupied by a range of party figures, from Mr Mwinyi’s successor, Benjamin Mkapa, to the incumbent Ms Hassan. Indeed, Mr Mwinyi himself appeared to be no stranger to dynastic politics: One of his sons, Hussein Ali Mwinyi, became president of Zanzibar in 2020, also representing Chama Cha Mapinduzi.

During his tenure, the elder Mr Mwinyi was credited with landmark reforms, including the licensing of mobile phones, computers and televisions. He pushed for higher prices for crops grown by peasant farmers and a greater role for private business.

In 1986, with his country on the brink of financial collapse, he signed an agreement with the International Monetary Fund to secure a $78 million reserve loan. It was Tanzania’s first such deal since a previous deal collapsed six years earlier. Several more agreements with the fund and the World Bank followed.

Mr Mwinyi’s decade in power coincided with the events that led to the end of the Cold War – a struggle that had rippled across Africa as rival camps jockeyed for influence in states aligned with distant donors in Moscow and the West. When one-party rule was officially dissolved in 1992, Mr Mwinyi said the transition to multi-party democracy reflected similar global developments.

Like other African leaders of his time, he criticized American foreign policy in Africa, saying that the Reagan administration’s reluctance to approve broader sanctions against white South Africa had created an obstacle to the effort to dismantle apartheid.

Nevertheless, his two terms have long been associated with a worsening of his country’s reputation for corruption, including scams to defraud a government debt service and the distribution of food deemed unfit for human consumption.

Under Mwinyi, according to a 2002 paper in the African Journal of Political Science, “corruption spiraled out of control.”

Ali Hassan Mwinyi was born on 8 May 1925, in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s commercial center and main port, to Hassan and Asha Sheikh Mwinyi. His parents were both originally from Zanzibar, where he spent much of his childhood, according to Tanzania’s foreign ministry.

He qualified as a teacher in Britain and taught in schools in Zanzibar before joining the government there as permanent secretary in the Ministry of Education. He went on to hold a number of government posts and from 1972 to 1974 represented Tanzania as its ambassador to Egypt, where he studied Arabic.

In 1960 he married Siti Mwinyi. One of their many children, Abdullah Mwinyi, a lawyer, credits his mother with supporting the family while his father was unemployed after serving as ambassador in Cairo.

“For a period of about two years our father was unemployed,” Abdullah Mwinyi wrote in a 2020 article. “Soon the ambassadors’ savings would run out. At the time, there were limited opportunities in commerce or any significant employment outside of government.”

He added, “Our mother decided to make lollipops (we had freezers from Egypt) and cook manantazis” — a type of fried doughnut-like bun — “to sell and preserve. Our mother through this venture was the food.”

Information about Mr Mwinyi’s survivors was not immediately available.

Mr Mwinyi became president of Zanzibar in 1984, before Mr Nyerere chose him as his successor the following year. He left office in 1995 after serving the maximum two terms set by the Tanzanian Constitution after 24 years of near-absolute power by Mr Nyerere. (Tanzania has held regular multiparty elections since its transition from a one-party state in the early 1990s.)

As a private citizen, Mr Mwinyi lived without ostentation and was photographed traveling on public transport.

In 2021, Mr Mwinyi published a memoir in Kiswahili, the title of which translates as ‘Mister Permission: The Journey of My Life’.

According to a review of the book published in The East African, a weekly news magazine, he said his primary legacy lay in the economic reforms that broke with the Nyerere era – a task, he said, “was by no means easy, but the change was needed.”

Abdi Latif Dahir contributed to the report.