In early February 2020, China locking over 50 million people, hoping to prevent the spread of a new crown. No one knew at that time exactly how it was spread, but Lidia Morawska, an air quality specialist at the University of Technology of Queensland in Australia, did not like the evidence he managed to find.

She looked at her as if the Koranus spread through the air, fluttering from the Wafting droplets, exhale from the infected. If this was true, then standard measures such as disinfection of surfaces and stay a few meters away from people with symptoms would not be enough to avoid infection.

Dr. Morawska and her colleague, Junji Cao at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, wrote a terrible warning. Violation of the virus air spread, they wrote, would lead to many more infections. But when scientists sent their comment to medical journals, they were rejected again and again.

“No one would hear,” said Dr. Morawska.

It took more than two years for the World Health Organization to officially recognize that Covid was spreading in the air. Now, five years after the start of Dr. Morawska listening to the alarm, scientists pay more attention to the way other diseases can also spread through the air. At the top of their list is the bird flu.

Last year, the disease control centers recorded 66 people in the United States infected by a bird flu executive called H5N1. Some of them probably got sick by handling birds loaded by viruses. In March, the Ministry of Agriculture discovered cows that were also infected with H5N1 and that animals could pass the virus to humans – probably through droplets splashed by milking machinery.

If bird flu wins the ability to spread from person to person, it could produce the next pandemic. Thus, some influenza experts are eagerly aware of the changes that could make the virus airborne, dragged into tiny droplets through hospitals, restaurants and other public areas, where his next victims could inhale.

“Having these elements are really important ahead of time, so that we do not end up in the same situation when Covid appeared, where everyone was trying to understand how the virus was transmitted,” said Kristen K. Coleman, an infectious-expert disease expert at the University by Maryland.

Scientists have supported how influenza has spread for over a century. In 1918, a flu executive called H1N1 swept the world and killed over 50 million people. Some American cities treated it as an airborne disease, demanding masks to the public and opening windows in schools. However, many public health experts remained convinced that the influenza was largely spread by direct contact, such as touching an infected door button or toasted or coughing.

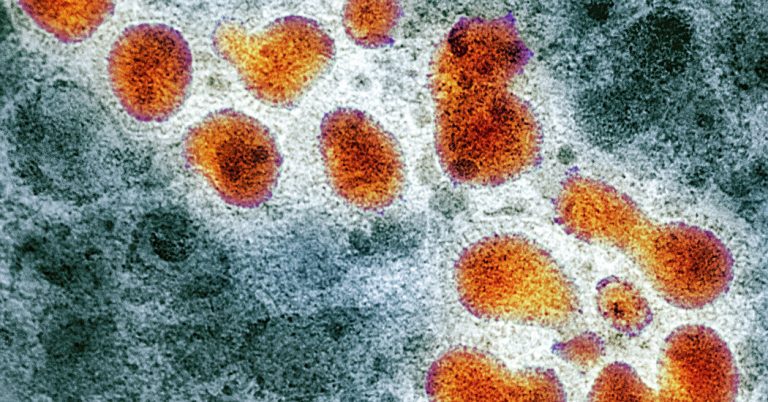

H5N1 came to light for the first time in 1996, when it was found in wild birds in China. The virus infects their digestive tracts and spread through their feces. Over the years, the virus has spread to millions of chickens and other farmed birds. Hundreds of people also get sick, mainly by handling sick animals. These victims developed H5N1 infections in the lungs that have often proved to be deadly. But the virus could not move easily from one person to another.

The threat of a H5N1 leak into human populations has prompted scientists to carefully consider how the influenza viruses spread. In an experiment, Sander Herfst, an Iologist at Erasmus Rotterdam University in the Netherlands, and his colleagues examined whether the H5N1 could spread between four inches in cages.

“Animals can’t touch each other. They can’t lick each other,” Dr. Herfst said. “So the only way to broadcast is through the air.”

When Dr. Herfst and his colleagues dug the H5N1 viruses in the ferrets of the Kunavians, they developed lung infections. They did not spread the viruses into healthy ferrets in other cages.

But Dr. Herfst and his colleagues discovered that some mutations allowed H5N1 to become a airborne. The genetically modified viruses that carried these mutations spread from one cage to another to three of the four tests, making healthy ferrets sick.

When scientists shared these results in 2012, there was an intense debate over whether scientists must deliberately try to produce viruses that could start a new pandemic. However, other scientists followed the research to understand how these mutations allowed the flu to spread into the air.

Some studies have shown that viruses become more stable so they can withstand a journey into the air in a droplet. When another mammal inhales the droplet, certain mutations allow the viruses to mourn in the cells in the upper air duct. And yet other mutations can allow the virus to thrive at the cool air duct temperature, making many new viruses that can then exhale.

Watching the flu between people has proved to be tougher, despite the fact that about one billion people get seasonal influenza each year. But some studies have highlighted the air transmission. In 2018, the researchers recruited college students ill with the flu and had breathed them into a horn -shaped airflow. The thirty -nine percent of the small droplets that exhale have brought viable influenza viruses.

Despite these findings, exactly how the flu spread through the air is still unclear. Scientists cannot offer an exact percentage of the percentage of influenza cases caused by the airborne spread against an infected surface like a pilot.

“Very basic knowledge is really missing,” Dr. Herfst said.

During last year, Dr. Coleman and her colleagues brought people sick with the flu to a hotel in Baltimore. Sick volunteers spent time in a room with healthy people, playing games and talking together.

Dr. Coleman and his colleagues gathered the influenza viruses floating around the room. But none of the non -infected volunteers were ill, so scientists could not compare how often the flu contaminates people through the air as opposed to short -range cough or virus -mentioned surfaces.

“It is difficult to imitate real life,” said Dr. Coleman.

While Dr. Coleman and his colleagues continue to try to expel the spread of influenza, bird flu is infecting more and more animals in the United States. Even cats are infected, possibly by drinking raw milk or eating raw pet food.

Some influenza experts are worried that H5N1 earns some of the mutations needed to go airborne. A virus isolated from a dairy worker in Texas had a mutation that could accelerate its reproduction to air ducts, for example. When Dr. Herfst and his colleagues were sprayed with ferrets with airborne droplets carrying Texas virus, 30 % of animals developed infections.

“Laboratories in the United States and around the world are on the alert to see if these viruses are approaching something that could be very dangerous to humans,” Dr. Herfst said.

It would be impossible to predict when – or even if – the viruses of the birds will win the additional mutations needed to spread quickly from person to person, said Seema Lakdawala, an Iologist at Emory University. But with the virus that runs ruthlessly on farms and so many people are infected, the chances of airborne evolution are increasing.

“What is shocking to me is that we let nature do this experiment,” Dr. Lakdawala said.