For more than 30 years, the Chinese premier’s annual press conference has been the only time a top leader has taken questions from reporters about the state of the country. It was the only chance for members of the public to highlight China’s No. 2 official. It was the only time some Chinese might feel a faint sense of political participation in a country without elections.

On Monday, China announced that the prime minister’s press conference, marking the end of the country’s annual parliamentary term, would no longer take place. With this move, an important institution of China’s reform era was no more.

“Welcome to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” wrote one commenter on the social media platform Weibo, reflecting the sentiment that China is increasingly resembling its dictatorial, hermitic neighbor. The search term “press interview” was censored on Weibo and very few comments remained as of Monday afternoon, Beijing time.

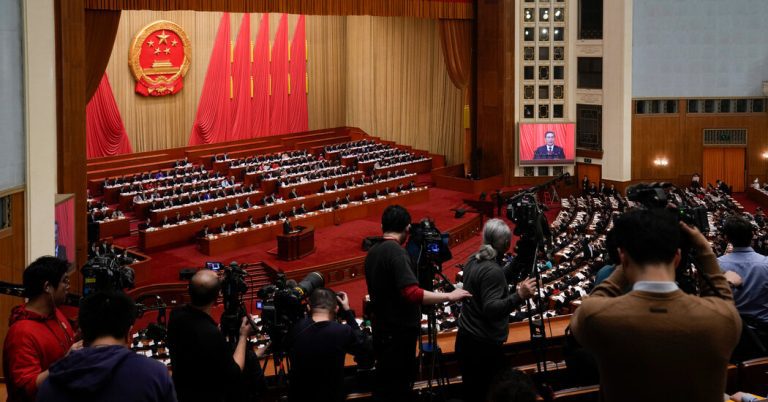

Although increasingly scripted, the premier’s press conference at the National People’s Congress was watched by the Chinese public and the global political and business elite for signs of a shift in economic policy and, occasionally, high-level power plays taking place below the surface.

“As far-fetched as it was, it was a window into how official China works and how official China is explained to the Chinese people and the wider world,” said Charles Hutchler, a former colleague of mine who attended 24 top press conferences. since 1988 as a reporter for the Voice of America, the Associated Press and the Wall Street Journal.

The decision to cancel the press conference reflects the dire economic conditions facing China and the leadership’s growing tendency to put the country in a black box. And there’s the obvious: Xi Jinping, China’s supreme leader, is the only person in charge of a country of 1.4 billion people.

The collapse of the press conference erased the last vestiges of the reform era.

In the 1990s and 2000s, China had two major televised events each year: the annual Lunar New Year televised gala and the annual press conference with the prime minister. (Think the Super Bowl and the Oscars in the United States, and even more so because China had few TV channels and the Internet was new.)

The first memorable political television moment for many Chinese was in November 1987. The outgoing premier, Zhao Ziyang, mingled with foreign correspondents at a reception at the end of the Communist Party Congress. Talkative and smiling, he answered questions: Was there a power struggle within the party between the reformers and the conservatives? Was there freedom in China? Where was his monochrome double suit made? Mr. Zhao, who was elected general secretary of the party at the congress, even said: “Personally, I believe that I am more suitable for the position of premier. But everyone wanted me to become general secretary.”

Such a public statement by a Chinese official would be unthinkable today.

Mr. Zhao was later fired for opposing the bloody crackdown on Tiananmen Square protesters in 1989. He died while under house arrest. The transfer and the video of the reception show that he avoided the questions, except for the one about his suit. (The suit came from a tailor shop in Beijing called Hongdu, or Red Capital.)

The premier’s press conference was instituted in 1993, but it did not become a must-watch television event until Zhu Rongji, a shrewd and good-humored premier, took the stage in 1998. Expressing his determination to become a good premier, he said : “Whether it’s a minefield or a bottomless abyss ahead, I will step forward without hesitation.”

This event was so popular that two people who participated in it gained national fame: a female reporter from a Hong Kong TV station who asked a question and a female Foreign Ministry official who interpreted for him in English.

Mr Zhu’s successor, Wen Jiabao, did not make big news in his press conferences until his last in 2012. Then he spoke of China’s need for political reform – the last time a top Chinese leader mentioned it – and heralded the fall of Bo Xilai, Mr Xi’s political rival.

Li Keqiang, who served as premier under Xi for a decade and was sidelined by his domineering boss for much of that time, made a point for transparency in 2020 when he said that about 600 million Chinese, or 43 percent of the population, earned a monthly income of about just $140. His comments poked a hole in Mr Xi’s claim that China was defeating poverty. When Mr Li died unexpectedly last October, many Chinese people took to the internet to thank him for telling the truth.

For the most part, the prime ministers used the venue to take questions from the international media and talk about economic and foreign policy. According to a 2013 article in a state-run publication, in the first press conferences held by Mr. Zhou, Mr. Wen and Mr. Li received almost half of the questions from foreign media.

The premier’s press conferences, attended by up to 700 journalists each year, were originally intended to provide interview opportunities for foreign media, allowing them to better understand China, the article said.

Under Mr Xi, the Chinese government has expelled and harassed foreign journalists, raided the offices of multinational companies and engaged in disputes with major trading partners. Closing the press conference will make China more isolated and less transparent to the outside world. This does not bode well for the economy.

One possible reason for the cancellation is that China is facing its most serious economic challenges in decades. But the country has gone through difficult times in the past, including the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s and the global financial crisis in 2008. Prime ministers then had no problems communicating the country’s policies to the public and the world.

At issue is how much China, under Mr. Xi’s leadership, values open communication. Media and internet censorship is the heaviest it has been in decades.

Many Chinese observers speculated that the demise of the press conference could be an attempt at self-preservation by the current premier, Li Qiang. Mr Li was Mr Xi’s chief of staff in eastern Zhejiang province in the 2000s and owes his position to Mr Xi.

Since taking office last March, Mr Lee has played down the stature and influence of his role. He was flying charter flights instead of the equivalent Air Force One, which he is entitled to, making Mr Xi the only one to enjoy the status. He reduced the frequency of meetings of China’s cabinet, chaired by the premier, from weekly to twice a month. His portraits do not appear on the cabinet website. Nor was he in the headlines on Tuesday when he delivered the government work report, an annual rite of passage for the prime minister. As usual, headlines and portraits of Mr. Xi dominated these sites.

Mr. Lee canceled his press conference, commentator He wrote in X, probably not because he lacks eloquence. “It was probably because Li Qiang felt that he would become the focus of the media at the press conference, overshadowing the brilliance of the General Secretary,” the commentator wrote, referring to Mr Xi. “He hopes to remain forever as the shadow Secretary General.”