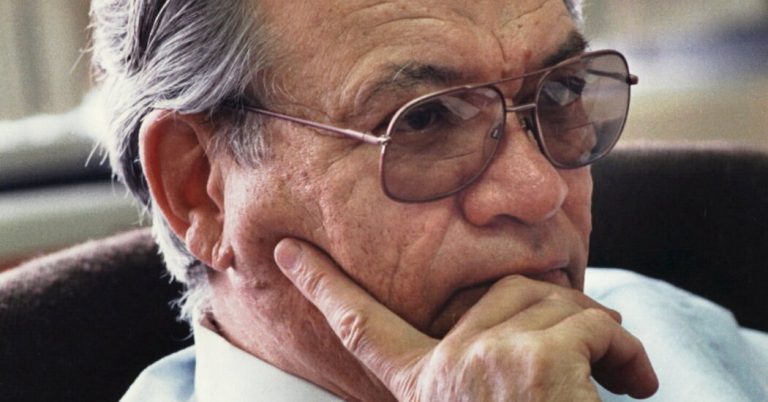

Anthony Insolia, a down-to-earth former Newsday editor who presided over the expansion of that Long Island newspaper and several major investigative projects, died Saturday in Philadelphia. It was 98.

His death, in a hospice, was confirmed by his stepdaughter, Robin Ireland.

Mr. Insolia was editor of Newsday from late 1977 until his retirement 10 years later, a period when the paper, a tabloid then owned by the Times Mirror Co., won seven Pulitzer Prizes, expanded its foreign reporting to several far-flung bureaus and cemented her reputation for hard-hitting street journalism close to home.

But it was an undertaking a year before he took over Newsday that was among his most significant journalistic achievements: what became known as the Arizona Project, a pioneering effort in collaborative journalism across multiple news organizations.

Mr. Insolia, who was Newsday’s editor at the time, was the story editor on the project, which was created in response to the 1976 murder of Arizona journalist Don Boles.

Mr. Bolles was fatally injured when his car blew up in a Phoenix parking lot in June 1976 as he investigated ties between Arizona politics, business and organized crime. A then-newly formed organization, Investigative Reporters and Editors, or IRE, assembled a team of 38 reporters from 28 news organizations under the leadership of Newsday reporter and editor Robert W. Greene to look into the circumstances of the murder and, he said. to make people “think twice” about killing journalists.

The project produced a series of 23 articles in 1977, all of which appeared in partner newspapers across the country, including The Indianapolis Star, The Tulsa Tribune, The Miami Herald, The Boston Globe and Newsday. Continuing Mr. Bolles’ work in trying to show those mob ties, the series “rocked the Arizona establishment to its foundations,” Ed DeLaney, a former IRE consultant, recalled in a 2008 article in the organization’s newsletter.

Mr. Insolia was also Newsday’s editor for a 1974 project, ”The Heroin Trail,” which traced the flow of heroin from the poppy fields of Turkey to suburban Long Island. He won the Pulitzer Prize for public service.

“He was very cautious, but he had big thoughts and dreams,” said Jim Mulvaney, who headed several foreign bureaus under Mr. Insolia. “He was a lover of good reporting. He would come and show him when you had done something good.”

The opposite was also true. Mr. Insolia was known for his uncompromising standards and “a relentless honesty that often crossed the line and earned him the nickname ‘Tony Insult,'” wrote Robert F. Keeler in the 1990 book “Newsday: A Candid History of the Respectable small-format newspaper.” He credited Mr. Insolia with “impeccable news judgment and relentless attention to detail.”

In a 1986 interview on C-SPAN, Mr. Insolia proudly discussed the recent hiring of New York Times columnist Sydney Schanberg as a columnist at New York Newsday, the newspaper’s New York branch (it closed in 1995, as did the newspaper’s foreign offices after all). Mr. Schanberg had left the Times after he suspended his column following his public criticism of the paper’s coverage of the Westway project, the proposed freeway on Manhattan’s West Side.

Asked whether Mr. Sandberg would face similar difficulties at Newsday, Mr. Insolia replied wryly: “These pages are here to represent as many points of view as possible.”

In the interview, he expressed complete confidence in the future of newspapers and their necessity, a crisis that predated the internet era. “The meat of a newspaper is explanatory,” Mr. Insolia said, adding, “I think people read newspapers and read them carefully.”

Anthony Edward Insolia was born on February 7, 1926 in Tuckahoe, New York in Westchester County. His father, Salvatore Insolia, an immigrant from Sicily, was a presser in the garment district of New York. His mother, Pasqualina (Beladino) Insolia, was a seamstress.

He attended schools in Mount Vernon, New York and was drafted into the Army in 1944, assigned to Tempelhof Airfield in Berlin as a radio ground station operator.

The first in his family to earn a college degree, Mr. Insolia graduated from New York University in 1949. He went to work as a reporter for The Yonkers Times while also working at a Gristedes supermarket. He moved to Newsday as a reporter in the fall of 1955 and remained there for more than 30 years.

In addition to his stepdaughter, Ms. Ireland, he is survived by his second wife, Jean Insolia; his daughters, Anne Smyers and Janet Insolia; his son, Robert; his brother, Richard; nine grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; and a stepson, David Uris.

“If there was a man who was temperamentally designed to be a journalist, it was him,” said Ms. Ireland, a former journalist herself who recalled his brutal honesty when she showed him her articles. Mr. Insolia’s catchphrase, he recalls, was: ”No one is going to tell you how great you are. You’ll have to do it yourself.”