Tommy Orange sat in front of a classroom in the Bronx, listening to a group of high school students discuss his novel “Over There.”

A boy wearing blue glasses raised his hand. “All the characters have some form of disconnection, even trauma,” said Michael Almanzar, 19. “This is the world we live in. They are all around us. It’s not like he’s in some faraway land. He’s literally your next-door neighbor.”

The class erupted into a series of finger snaps, as if we were in an old poetry school on the Lower East Side rather than an English class at the Millennium Art Academy on the corner of Lafayette and Pugsley avenues.

Orange accepted it all with a mixture of gratitude and humility—the semicircle of earnest, dedicated teenagers. the bulletin board emblazoned with words describing ‘There’ (‘hope’, ‘struggle’, ‘mourning’, ‘discovery’); the shelf of good-looking copies wearing dust jackets in various stages of decay.

Eyebrows were raised when a student wearing a sweatshirt that read “I Am My Ancestors’ Wildest Dreams” compared the book to Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road.” When three consecutive students talked about how they related to Orange’s work because of their own mental health struggles, he was on the verge of tears.

“That’s what drew me to reading in the first place,” Orange said, “The feeling of not being as alone as you thought you were.”

It’s not often that a writer walks into a room full of readers, let alone teenagers, who talk about characters born in their imagination as if they were living human beings. And it’s just as rare that students spend time with an author whose fictional world feels like a sanctuary. Of all the classroom visits he’s made since releasing There There in 2018, the one at the Millennium Art Academy earlier this month was, Orange later said, “the most intense connection I’ve ever experienced.”

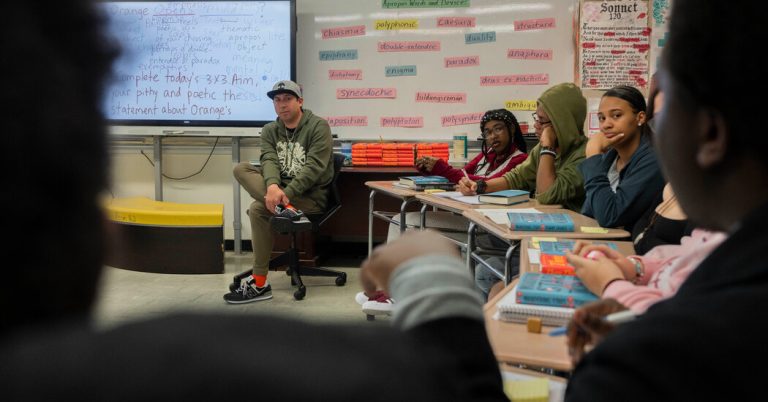

The catalyst for the visit was Rick Ouimet, an active English teacher with a ponytail who has worked in the fortress-like building for 25 years. Ouimet is the kind of teacher students remember, whether it’s for his contributions to their literary vocabulary – synecdoche, bildungsroman, chiasmus – or his battered mobile phone.

He first learned about “There There” from a colleague whose son recommended it during the pandemic. “I knew from the first paragraph that this was a book that our kids were going to connect with,” she said.

The novel follows 12 characters from indigenous communities who lead a powwow at a stadium in Oakland, California, where tragedy strikes. “Orange takes you to the drawbridge, and then the opening starts to rise,” New York Times critic Dwight Garner wrote when it was released. The novel was one of the Times’s 10 Best Books of 2018 and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. According to Orange’s publisher, over a million copies have been sold.

Ouimet’s hunch turned out to be true: “Students love the book so much, they don’t realize they’re reading it for English class. This is the rare find, the gift of gifts.”

Some relevant stats: Participation rates at Millennium Art are below the city average. Eighty-seven percent of students are from low-income households, which is above the city average.

In the three years since Orange’s novel became a mainstay of the Millennium Art curriculum, pass rates for students taking Advanced Placement literature exams have more than doubled. Last year, 21 out of 26 students earned college credit, beating state and global averages. The majority of them, Ouimet said, wrote about “There there.”

When three students in the school’s art-adorned hallway were randomly asked to name a favorite character from “There There,” they all responded without hesitation. It was as if Tony, Jacquie and Opal were people they could meet at ShopRite.

Briana Reyes, 17, said, “I connected so much with the characters, especially having family members with alcohol and drug abuse.”

Last month, Ouimet learned that Orange, who lives in Oakland, was going to be in New York to promote his second novel, “Wandering Stars.” An idea began to percolate. Ouimet had never invited a writer to his class before. such visits can be expensive and, as he pointed out, Shakespeare and Zora Neale Hurston are not available.

Ouimet composed a message in his head for more than a week, he said, and on Monday, March 4, shortly after midnight, he sent it to Penguin Random House’s speakers bureau.

“The email looked like a rough draft, but I didn’t struggle,” he said. “It was my middle age essay in college.”

The 827-word dispatch was written in the style Ouimet encourages in his students’ work, full of personality, texture and detail, without the corporate speak that permeates so much Important Business Correspondence.

Ouimet wrote: “In our 12th grade English class, in our diverse corner of the South Bronx, in an under-resourced but vibrant urban neighborhood not unlike Fruitvale, you are our rock star. Our more than rock star. You are our MF Doom, our Eminem, our Earl Sweatshirt, our Tribe Called Red, our Beethoven, our Bobby Big Medicine, our email to Manny, our ethnically ambiguous woman in the next stall, our camera points into a tunnel of darkness. “

Orange, he added, was a hero to these children: “You have changed lives.” It was Tahqari Koonce, 17, who drew a parallel between the Oakland Coliseum and the Roman Colosseum. and Natalia Melendez, also 17, who noted that a white gun symbolized the oppression of indigenous tribes. And then there was Dalvin Urena, 18, who “said he’d never read an entire book until ‘There,'” and now compared it to a Shakespeare sonnet.

He ended with: “Well, it was worth a shot. Thanks for taking the time to read this — if it ever finds you. Sincerely (and in awe), Rick Ouimet.”

“I took a chance,” Ouimet said. And why not? “My students have an opportunity every time they open a new book. There is a groan and they turn the page. To see what they gave this book? The love was palpable.”

Within hours, word reached Orange, who was in the middle of a 24-city tour with multiple interviews and events each day. He asked Jordan Rodman, senior director of publicity at Knopf, to do what he could to squeeze Ouimet’s class into the mix. There would be no charge. Knopf donated 30 copies of “There There” and 30 copies of “Wandering Stars”.

In a large, bustling school filled with squeaky soles, walkie-talkies and young people, moments of silence are hard to come by. But when Orange opened his new novel, you could have heard a pin drop.

“It’s important to say things, to express them, like the way we learn to spell by saying words slowly,” Orange said.

He continued: “It is just as important for you to hear yourself tell your stories as it is for others to hear you tell them.”

The students followed their own copies, heads bowed, necks looking vulnerable and strong at the same time. Their intent proved that, like the spiders described in There There, books contain “miles of history, miles of possible home and trap.” On this indescribably gray Thursday, Orange’s play offered both.

After the 13-minute reading came the questions, fast and furious, phrased with refreshing bluntness: “What inspired you to write these two books?” and “Is Octavio dead?” and, perhaps most pressingly, “Why did ‘There There’ end like this?” Not since “The Sopranos” has an ambiguous withdrawal caused more concern.

“We were like aaaaah?” said one student holding the last word on a high note.

“It was a tragic story,” Orange said. “Some people hate it and I’m sorry.”

He admitted to being a non-reader in high school: “Nobody handed me a book and said, ‘This book is for you. I also had a lot of stuff at home.” He talked about how he gets rid of writer’s block (changing points of view), how he reads his drafts out loud to hear how they sound. Orange shared his name Cheyenne – Birds Singing in the Morning – and introduced a childhood friend who travels with him on tour.

Amidst all this, Ouimet stood quietly at the side of the room. He gave a soft dirty eye to a bunch of chattering girls. He used a long wooden pole to open a window. Mostly, he just beamed like a proud parent at a wedding where everyone is dancing.

The truth is that “There There” didn’t just cast a spell on his students: it also had a profound effect on Ouimet himself. When he started teaching the book, he had just retired from coaching football and softball after 22 years.

“I was afraid: If I don’t have coaching, will I still be an effective teacher? “There There” was that kind of revival. I don’t want to be too dumb,” he said, “but it was kind of career-saving.”

Finally the bell rang. Students pushed back from their desks and lined up to have their books signed by Orange, who took a moment to chat with each one.

Over the hum, to anyone still listening, Ouimet shouted, “If you love a book, talk about it! If you love a story, let others know!”