The public got a first look Monday at a CIA “black site,” including a windowless, closet-sized cell where a former al Qaeda commander was held during what he described as the most humiliating experience of his time in U.S. custody .

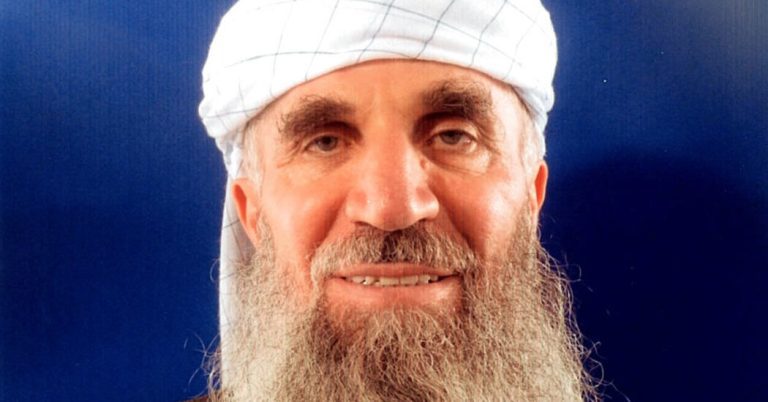

The former commander, Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, led the 360-degree virtual tour of the site, Quiet Room 4, during a sentencing hearing at Guantanamo Bay that began last week. He described being blindfolded, stripped, forcibly shaved and photographed naked on two occasions after his arrest in 2006.

He never saw the sun, nor heard the voices of his guards, who were dressed entirely in black, including their masks.

Mr. Handy, 63, was one of the last detainees in the Black Abroad network where the George W. Bush administration held and interrogated about 100 terror suspects after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

Even now, years after the Obama administration shut down the program, its secrets remain. But the details are slowly emerging in the national security trials of former Guantanamo detainees.

In court on Monday, viewers saw Quiet Room 4, an empty 6-square-foot cell, which Mr. Hadi said looked like the place he was held for three months – minus a bloodstain that was then on the wall of his cell.

It was a great moment. Mr. Hadi addressed the US military commission from an upholstered therapy chair that he uses because of a paralyzing spinal disease. He slowly read an unclassified English language script, pausing a few times to regain his composure or wipe tears from his eyes.

Mr. Hadi described his situation as harsh, but said his experience as a United States prisoner had been tempered by remorse and forgiveness.

In 2022, the prisoner pleaded guilty to war crimes. Addressing jurors on Monday, he apologized for the unlawful behavior of Taliban and Qaeda forces under his command in wartime Afghanistan in 2003 and 2004. Some used civilian cover for attacks such as turning a taxi into a car bomb. Others became suicide bombers or shot at a medevac helicopter.

“As a commander I take responsibility for what my men did,” he said in a 90-minute presentation. “I want you to know that I have no hatred in my heart for anyone. I thought I did the right thing. I was not. I am sorry.”

Speaking about his time in CIA custody, Mr Hadi described the months after his capture in Turkey in late 2006, when he disappeared into the last remnants of the black site program in Afghanistan, until April 2007.

At first he was held in a windowless cell with a built-in, stainless steel shower and toilet, according to court visuals. He became emotional after months of constant questioning about the location of Osama bin Laden, which he said Monday he did not know.

The next cell, shown in court, was empty, with no toilet or shower — just three tie-down points on the walls. For the three months he was held there, Mr Hadi said, he had a thin mat on the floor, a bucket for a toilet and a spatter of bloodstains on one wall.

At one point, he said, his portion contained pork, which is forbidden in Islam. He refused to eat and became so weak that he could not stand. His captors then brought him a diet substitute, Ensure. He saw no sunlight and had no watch to know when to pray, he said.

The images, if not the testimony, stunned a government lawyer. When Mr. Hadi’s lawyers began examining images from cells similar to those in which he was held incommunicado in 2006 and 2007, a prosecutor protested, only to learn that the footage had recently been declassified.

The existence of the forensic photo was first revealed in 2016 in the 9/11 case. Prosecutors gave defense attorneys the material, but did not reveal the location of the program’s last known intact black site prison. Monday’s testimony made it clear that he was in Afghanistan.

The jury will sentence Mr. Hadi to 25 to 30 years in prison. But the sentence could be shortened by US officials.

After another former CIA detainee, Majid Khan, was allowed to describe his torture at his sentencing hearing in 2021, the jury returned a 26-year sentence. But the panel also recommended he receive clemency because of his abuse in the US. Mr. Khan has since resettled in Belize and reunited with his family.

Last week, victims of attacks by Mr. Hadi’s forces testified about their continued grief over the emotional and physical damage they suffered in the early years of America’s longest war. On Monday, Mr Hadi spoke directly to them.

“I know what it’s like to see another soldier die or be injured,” he said. “I know that feeling and I’m sorry. I know you suffered a lot.”

It seemed to single out a Florida man, Bill Eggers, who spoke of losing his firstborn son, a commando, to a roadside bomb planted by Mr. Handy’s troops in 2004. “I know what it’s like to be father of a son. ‘ he said. ‘To lose your son – your grief must be overwhelming. I’m sorry.’

Mr Hadi opened his address to the jury by apologizing for sitting in the padded healing chair, rather than standing and addressing them. “I have problems with my spine,” he said.

When Mr. Hadi was first brought to court in 2014, he went to court with military police at his side. He is now crippled by degenerative disc disease that, after six surgeries, some unsuccessful, has left him reliant on painkillers, a wheelchair and a four-wheeled walker to get around.

He described his 17 years in prison at Guantanamo as lonely at times, an isolating experience interspersed with isolated acts of kindness. While he was recovering from his surgeries, he said, the prison staff nurses “took care of me with kindness.”

During a period when he was paralyzed, he said, a US military doctor helped house him in his prison cell and “came to play checkers with me, stay with me while I was recovering from surgery.”