Five years ago Italian researchers published a study on the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which describes in detail how a victim of the explosion, a male supposed to be in the mid -1920s, had been found near the seaside settlement of Herculaneum. He was lying forward and buried from ash in a wooden bed at Augustales College, a public building dedicated to the worship of Emperor Augustus. Some scholars believe that the man was the foreman of the center and was sleeping at the time of the disaster.

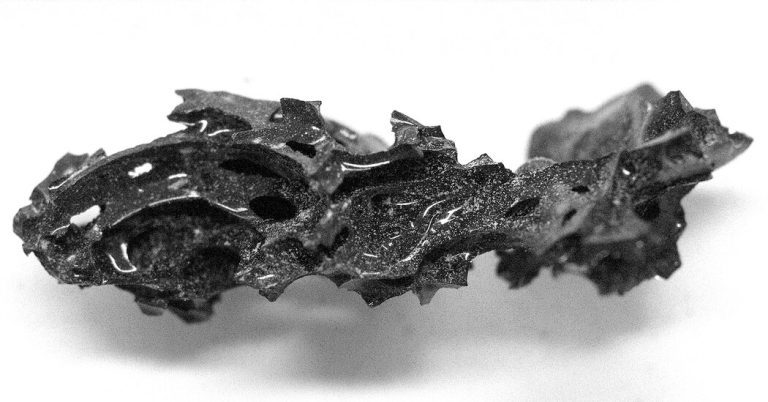

In 2018, a researcher discovered black, glossy fragments integrated into the guard’s skull. The document, published in 2020, expressed the speculation that the heat of the explosion was so huge that it had merged the victim’s brain tissue.

The forensic analysis of obsidian chips revealed proteins common to the brain tissue and the fatty acids found in human hair, while a piece of wood discovered near the skeleton showed thermal reading as high as 968 degrees Fahrenhein. It was the only known case of soft tissue – much less any organic material – which is naturally preserved as glass.

On Thursday, a document published in nature verified that the fragments are actually a polished brain. Using techniques such as electron microscopy, X -ray spectroscopy, and differential scanning, scientists examined the physical properties of the samples obtained from the glass fragments and showed how they were formed and preserved. “The only finding implies unique processes,” said Guido Giordano, a volcanic at the University of Roma Tre and lead author of the new study.

First of all, these procedures is the vitrification, with which the material burns at high temperature until it is liquefied. To harden in glass, the substance requires rapid cooling, solidifying at a temperature higher than its environment. This makes the organic glass formation provocative, Dr. Giordano said, as glassing implies very specific temperature conditions and the liquid form should cool down quickly to avoid crystallize as canned.

Dr. Giordano and his colleagues suggested that shortly after the start of Vesuvius that began the wreckage, a toxic cloud of ash and white sign shining through Herculaneum, immediately killing its inhabitants. Claudio Scarpati, a volcanic at the University of Naples Federik II, suggested that this so -called fireproofing stream was the third of the 17 that fell from Vesuvius.

Pulses of colder volcanic debris followed, flooding the area. “Herculaneum residents were already dead since they were buried,” Dr. Giordano said.

Although the short -lived cloud of ash left only one inch or two of the debris and minimal, if any structural damage is said to have warmed the guard’s brain to well over 950 degrees, the glass transition temperature. This broke the soft tissue into smaller pieces without destroying it. Dr. Giordano said that the bones of the skull and the spine of the man probably gave some protection to the brain.

As the ash cloud dissolved, temperatures quickly returned to normal. In the outdoor air, at 950 degrees, the brain of the guardian fossilized into glass. Only the parts of the body containing some liquid can glass, said Dr. Giordano, so the guard’s bones remained intact.

The study of 2020 met with some skepticism from other scientists, mainly because raw data were not available. Tim Thompson, a criminal anthropologist at Maynooth University in Ireland, was perhaps the most vocal challenge. This time, the results were excited. “I love to see new scientific methods applied to the archaeological context,” he said.

But Dr. Thompson would like to see more information and more of the initial data: “Herculaneum heating and cooling after the explosion is likely to be complicated and the results of the research certainly support their conclusions. It simply depends on whether the material is brain.”