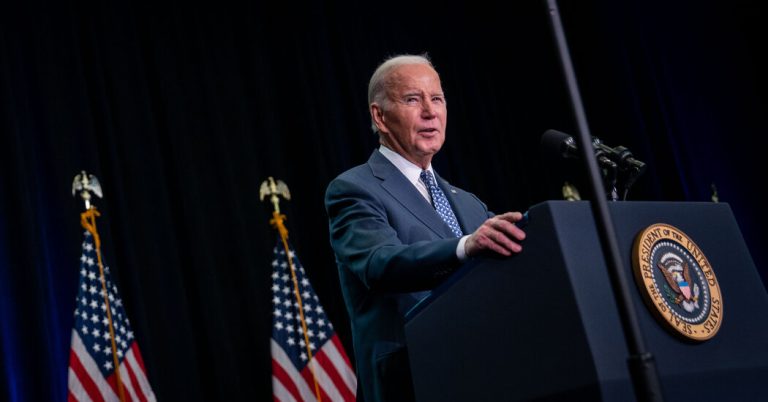

A lengthy Justice Department report on President Biden’s handling of classified documents contained some startling assessments of his well-being and mental health.

Mr. Biden, 81, was an “elderly man with a poor memory” and “reduced abilities” who “didn’t remember when he was vice president,” said special counsel Robert K. Hurr.

In conversations recorded in 2017, Mr. Biden was “often painfully slow” and “struggled to recall events and struggled at times to read and communicate his own notebook entries.” Mr. Biden was so weakened that a jury was unlikely to convict him, Mr. Hurr said.

Republicans were quick to pounce, some calling the president unfit for office and demanding his removal.

But while the report discredited Mr. Biden’s mental health, doctors on Friday noted that her judgments were not based on science and that her methods bore no resemblance to those doctors use to assess possible cognitive decline.

In its simplest form, the question is one that doctors and family members have grappled with for decades: How do you know when an episode of confusion or a memory lapse is part of a serious decline?

The answer: “You don’t,” said David Loewenstein, director of the center for cognitive neuroscience and aging at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Diagnosis requires a series of sophisticated and objective tests that investigate several areas: different types of memory, language, executive function, problem solving and spatial skills, and attention.

The tests, he said, determine whether a medical condition is present and, if so, its nature and extent. Verbal stumbles are not proof, said Dr. Loewenstein and other experts.

“Forgetting an event doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a problem,” said Dr. John Morris, a professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis.

Mr Hur, the special adviser, based his conclusions on a five-hour interview conducted over two days – the two days after Hamas’s surprise attack on Israel – and a review of interviews with a ghostwriter recorded in 2017.

But to scientifically identify a memory problem requires doctors to assess the change in a person’s cognitive function over time and determine that its magnitude is sufficient to impair the patient’s ability to perform normal activities, Dr. Morris said. .

The best way to determine whether such a change has occurred is to compare results from a memory test today with results from a test taken five or 10 years ago, he added. Otherwise, doctors can interview someone who knows the patient well—usually a close family member—to figure out if there was a fall.

Recall is only one aspect of cognition, noted Dr. Mary Ganguli, professor of psychiatry, neurology and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

To make an accurate diagnosis, a geriatric psychiatrist may ask how long the patient has had problems with the ability to plan and organize or express themselves. If the person is forgetful, what does the person forget and when?

“We want to know what specific losses were observed, not just ‘memory,'” Dr. Ganguly said. “Was it a one-time thing when the person was tired or sick, or is it happening all the time and increasing in frequency?”

It’s important to rule out other possible causes that may affect cognitive function, such as a stroke or head injury, or even the use of certain common medications, Dr. Ganguli added.

For example, a common culprit in memory lapses is diphenhydramine (sold as Benadryl and other brands). People who take chronic naps often forget as a result. (Her patients often tell her they take Tylenol at night, she said, but Tylenol PM actually contains diphenhydramine.)

In particular, Alzheimer’s has a distinctive pattern of memory loss, which should not be confused with ordinary forgetfulness, Dr. Ganguli added. A person with the disease usually forgets recent events, such as what they had for breakfast, but remembers things from the distant past, such as a wedding day.

A thorough examination can take an hour, Dr. Ganguli said, and may additionally include interviews with family members. A family doctor can do a more brief assessment, including quick memory tests like the Mini Mental State Examination or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, known as the MoCA.

In these tests, patients are asked the date and time and ask for the location of the practice. They may be asked to draw a clock that shows a specific time. They are told several words and, after a while, they are asked to repeat them.

To assess cognitive status, Dr. Loewenstein often administers a much longer, more probative series of objective tests. It’s a cardinal principle of the field to never diagnose a patient you haven’t seen in a medical setting, he said.

Dr. Loewenstein said he was outraged at specialists “who would have the audacity to make diagnoses saying, ‘Oh, this person went to the refrigerator and forgot why,’ or ‘Oh, they replaced someone’s name with another name when they had another name.'” things on their minds.”