Inflation picked up slightly in February on an overall basis and a measure of underlying price increases was firmer than economists had expected.

The new data underscore that a full return to normal inflation is likely to be a bumpy process — and support the Federal Reserve’s decision to proceed cautiously as officials consider when and how much to cut interest rates.

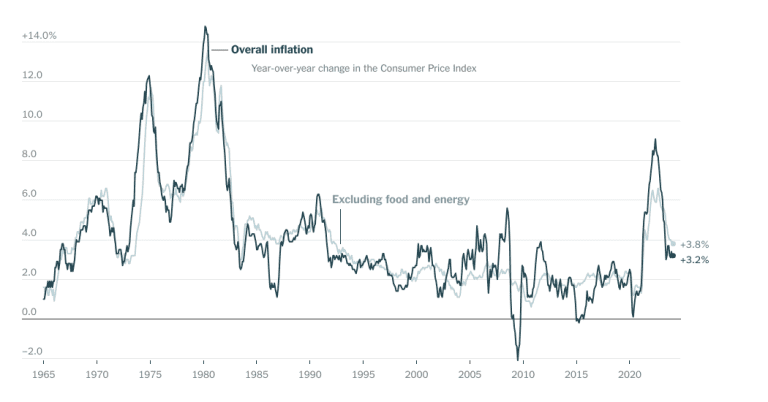

The Consumer Price Index rose 3.2% last month from a year ago, up from 3.1% in January. That’s significantly lower than a high of 9.1 percent in 2022, but still faster than the roughly 2 percent that was normal before the pandemic.

After stripping out volatile food and fuel costs to get a better sense of the underlying trend, inflation came in at 3.8%, slightly faster than economists had forecast. And on a monthly basis, core inflation rose slightly faster than expected as airline and auto insurance prices rose, even as a closely watched housing measure rose less quickly.

Overall, the report is the latest sign that fully reducing inflation is likely to take time and patience.

“It’s just going to underscore the Fed’s cautiousness about the outlook for inflation,” said Kathy Bostjancic, chief economist at Nationwide Mutual.

To date, inflation has been falling steadily and relatively painlessly: unemployment remains below 4% and growth in 2023 has been unexpectedly strong, even as the Fed raised interest rates to a more than two-decade high.

Fed officials are debating how long they need to leave interest rates at their current level of around 5.3%. Increased borrowing costs make it expensive for people to borrow to buy a home or expand a business, and that can weigh on the economy over time. The Fed is trying to reduce demand enough to bring inflation under control, but officials want to avoid crushing growth to the point that it leads to widespread job losses or a recession.

Some economists worry that it could be harder to slow inflation the rest of the way than it has been to achieve progress so far. And Fed officials want to avoid cutting interest rates too soon, only to find out that inflation hasn’t been completely eliminated.

“We don’t want to have a situation where it turns out that the six months of good inflation data we had last year didn’t turn out to be an accurate sign of where underlying inflation is,” Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chairman, said in testimony before of Congress last week. Since, he said, the Fed is being cautious.

But Mr. Powell also said last week that once the Fed was confident that inflation had fallen enough – “and we’re not too far from that,” he added – then it would be appropriate to cut interest rates.

“Overall, the view that deflation is in the economy — that’s still intact,” Ms. Bostjancic said after the new inflation report. “But it’s keeping them on hold to really have that confidence that they’re going to have to start cutting rates.”

The Fed is targeting annual inflation of 2%. It sets this target using a separate but related measure of inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditure measure. This index incorporates some data from the CPI data, but appears with a longer delay.

Some economists questioned whether price increases would continue to ease smoothly toward the central bank’s target. If inflation for services – such as housing and insurance – turns out to be more persistent than expected, it could make it more difficult to fully eliminate across-the-board price increases.

The report released on Tuesday offered some good news in that regard. A closely watched measure that effectively tracks how much it would cost to rent a home someone owns rose more modestly. Economists have been nervously watching this measure of “equivalent landlord rent” after it accelerated in January.

Capital home rent, on the other hand, rose slightly faster to 0.5% month-on-month, compared with 0.4% in January.

“It had fallen so much last month that I’m not at all worried about the recovery,” Laura Rosner-Warburton, senior economist at MacroPolicy Perspectives, said of the rent pickup. He said that together, the landlord’s rent and rent measures “tell a story of housing cost moderation”.

Commodities have been detracting from inflation lately, but there were some exceptions in February. Clothing prices dipped recently on a monthly basis, for example, but rose in cost last month.

Fed officials meet on March 19-20 and are widely expected to leave interest rates unchanged at that meeting. They will release a new set of economic forecasts after the meeting, which will show how much they expect to cut rates in 2024. According to their latest estimates, released in December, officials expected to make three rate cuts this year.

Investors believe the Fed could start cutting interest rates in June, later than they expected earlier this year.

“We still believe there is enough deflationary pressure to fuel,” economists at Capital Economics wrote in a note reacting to the report. They still believe the Fed will start cutting interest rates in June, “by then there will be more evidence” of further easing.