Howard Bouten, a college dropout from Detroit, has lived three extraordinary lives.

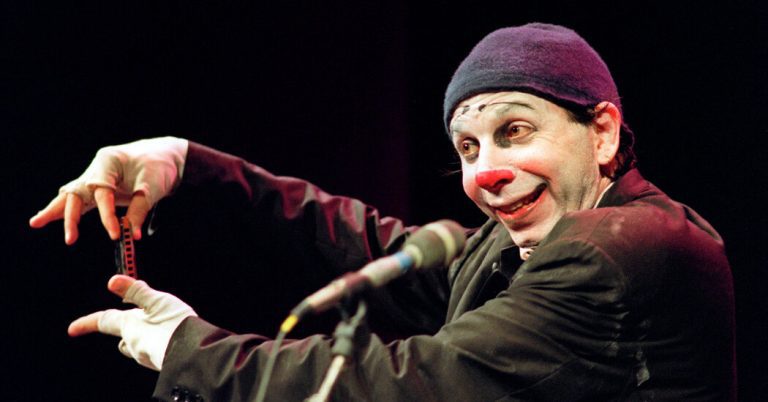

In one, he was a cuddly, clumsy and speechless red-nosed clown named Buffo. It sold out theaters around the world. Critics compared him to Charlie Chaplin and Harpo Marx.

In another, he volunteered as an aide with autistic children, went back to school to earn a doctorate in psychology, helped pioneer a treatment for autism, and opened a treatment center.

He turned to a third life as a novelist. “Burt,” written in the voice of a disturbed 8-year-old boy, flopped in the United States, but failed miserably to “Catcher in the Rye” status in France, where it sold nearly a million copies and became – to his amusement and a slight chagrin – a cultural sense.

“Howard Boutin is a kind of walking poem,” wrote the French writer and actor Claude Dunnetton in his introduction to Mr. Boutin’s autobiography, “Buffo” (2005). “Images come from him, producing a slow music, a concentric adagio like ripples on water.”

Mr. Buten died on January 3 at an assisted living facility near his home in Plomodiern, France, a town in coastal Brittany. It was 74.

His partner and sole immediate survivor, Jacqueline Huet, said the cause was a neurodegenerative disorder.

The three lives of Mr. Buten joined when he moved to France in 1981 after the unexpected success of “Burt,” which was released in French under a new title, “When I Was Five Killed Myself” — the first sentence of the novel.

On the day, Mr. Buten volunteered at an autism clinic before establishing his own center in Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris. At night, in nightclubs and theaters was Buffo — an act that in 1998 won a Molière, the equivalent of the Tony Award. He wrote novels in spare moments in coffee shops, on trains and in the back seats of taxis.

To organize his studious life, Mr. Bouten used a color-coded system in his diary: yellow and orange ink for Bufo performances, black for appointments at the autism center, blue to exclude time for writing. “I manage these three aspects of my life quite well,” he told Swiss newspaper Le Temps in 2003. “They are all essential to me.”

They were not as dissimilar as they might seem.

After leaving the University of Michigan in 1970, Mr. Buten was written at Ringling Bros. tribute to famous swiss clown Grok, pantomime, white face playing haploton musical instruments.

A star was not born.

“Howie wasn’t going anywhere,” his childhood friend Jim Bernstein, director of the University of Michigan’s screenwriting program, said in an interview. “He wrote a novel that no one wanted. His girlfriend broke up with him. His dog, Frank, was hit. He was in a horrible place.”

Hoping to succeed by doing some good in the world, Mr. Buten volunteered at a center for developmentally disabled children in Detroit. This was in 1974, six years before the criteria for diagnosing autism were established by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

The first child he met was a 4-year-old named Adam Shelton.

“He bit and head-butted, pinched and punched, himself as well as others,” wrote Mr. Buten in Through the Glass Wall: Journeys Into the Closed-Off Worlds of the Autistic (2004). “He had no tongue. He did not come when called. He wouldn’t sit still in a chair.”

Mr. Bouten worked with Adam almost every day. Unable to contact him, Mr. Bouten decided to imitate his actions – “I shake when he shakes, clap my hands when he claps his hands, scream and hum when he screams and hums,” she wrote.

One day, Adam began to imitate him.

Interested, Mr. Buten continued the approach, eventually using imitation to teach Adam acceptable social behaviors and more than a dozen words. Although the method Mr. Buten stumbled upon was not entirely new, studies have shown that the technique – called reciprocal imitation training – is a useful treatment for autism.

While treating Adam, Mr. Buten also stumbled upon a persona of Buffo: a clown who can sing and make noise, but cannot speak.

“What I learned is how to be autistic,” said Mr. Buten in The San Francisco Examiner in 1981. “He goes right to Buffo – his mannerisms, speech patterns (or lack thereof), physical behaviors and perceptions of reality are all truly autistic. A kind of stupid syndrome is what Buffo is: lovable, infantile, completely innocent.”

Adam was also on the mind of Mr. Buten when he wrote “Burt” (1981), which sold less than 10,000 copies in the United States but is still read in French schools.

“This is a child who is in a mental institution and is believed to be disturbed,” said Mr. Buten in The Detroit Free Press in 1981. “I wrote it from the kid’s own point of view because I don’t think he’s disturbed. He added, “The theme of the book is a statement about how adults generally don’t understand children, even though they used to.”

Early in the novel, Bert wanders the institution alone.

“I was sleepy,” Burt says. “I sat on my bed. It has sheets. It’s a mess at home. It’s blue. I’ve had him since he was a baby. My mom wants to throw him away but I won’t let her. But once I did something. I peed on the blankee. It smelled very spicy.”

Howard Alan Booten was born on July 28, 1950 in Detroit. His father, Ben Buten, was a lawyer. His mother, Dorothy (Fleisher) Buten, was a tap dancer and vaudeville performer growing up.

Howie was precocious and artistic.

After his mother taught him to sing and dance, he taught himself to be a ventriloquist. His first gig was in a synagogue “as a sort of junior cantor,” he told The San Francisco Examiner. “I thought it was religious, but it was really showbiz.”

He majored in Far Eastern studies at the University of Michigan, but spent most of his time skipping class and clowning around. Determined to pursue a career in real-life clowning, Mr. Buten did the math.

“I could go to clown college for 13 weeks and be a clown,” he told his friends. “Or I could go to the University of Michigan for two more years and be a clown.”

Although he never finished college, he earned a doctorate in clinical psychology from Fielding Graduate University in Santa Barbara, California in 1986, his clinic, the Adam Shelton Center, opened in 1996. “Burt” was reissued in the United States in French of the title in 2000, this time in a new estimation.

“Bert narrates in one of the most charming voices since Holden Caulfield,” Rick Whittaker said in a review for the Washington Post, adding that Mr. Bouten was “too good to be left to the French.”

The French adored Mr. Boutin in a way that the Americans never did, a mystery that would preoccupy him throughout his life. They made him a Knight of Arts and Letters by the French Ministry of Culture in 1991.

Mr. Buten returned to the United States sporadically to perform as Buffo. In 2004, he played a two-night stand at Cal State LA’s State Playhouse—performances a Los Angeles Times review described as “a sweet whirlwind of existential silliness and sage understanding.”

Culture Clown, a French magazine, once asked him what happened when he left the stage.

“Buffo disappears and Howard comes back,” he said. “That’s why I feel uncomfortable during the applause – Baffo is shy and Howard doesn’t like to take credit for himself.”