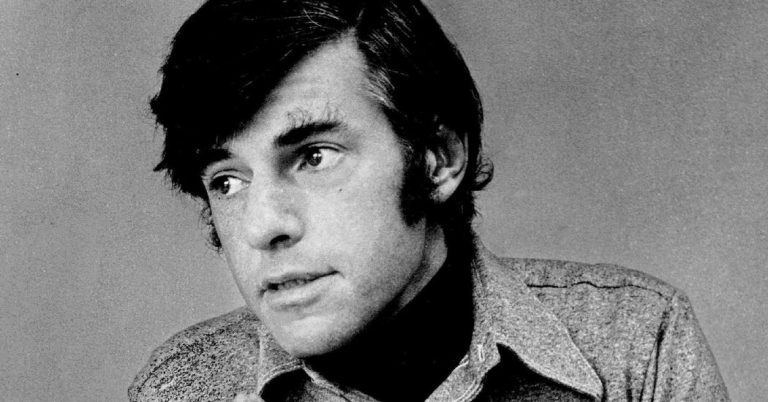

H. Bruce Franklin, a self-described Maoist whose dismissal from Stanford University in 1972 for an anti-Vietnam War speech became a cause for academic freedom — and who in the following decades wrote books on eclectic subjects, including one credited with helped improve the ecology of New York Harbor — died May 19 at his home in El Cerrito, California, near Berkeley. He was 90.

The cause was corticobasal degeneration, a rare brain disease, his daughter Karen Franklin said.

Dr. Franklin was a tenured English professor and author of three scholarly books on Herman Melville when he was radicalized in the 1960s by the Vietnam War, a process accelerated after he spent a year in France, where he and his wife, Jane Franklin. , he met Vietnamese refugees whose relatives had been killed by American forces.

“When we came back to this country, we were Marxist-Leninists and we saw the need for a revolutionary force in the United States,” Dr. Franklin told the New York Times in 1972.

His far-left politics, to the point of endorsing violence, reflected the extreme currents running through the country and culture of the time, a mixture of revolutionary theatrics and genuine menace.

Back at Stanford, he and his wife helped form a group called the Peninsula Red Guard. Dr. Franklin was also a member of the central committee of Venceremos, a local organization promoting armed self-defense and the overthrow of the government.

During the unrest on the Stanford campus in February 1971, Dr. Franklin urged the students to shut down “that most obvious war machine”: the Stanford Computing Center, which was believed to be engaged in war-related work. A crowd of people stormed the building and cut off the electricity.

At the urging of the university’s president, Richard W. Lyman, a faculty board voted to fire him for inciting violence.

Dr. Franklin defiantly responded by holding a press conference with his wife, who, brandishing an empty M1 rifle carbine, to show “that’s where political power comes from,” he announced, a reference to a saying by Mao Zedong.

His firing was the first dismissal of a tenured professor at a major university since the McCarthy era and sparked a national debate about academic freedom. Alan M. Dershovich, then a young civil liberties lawyer spending a year at Stanford, argued that Dr. Franklin’s speech to the students was protected by the First Amendment. Nobel laureate chemist Linus Pauling denounced what he called “a major blow to free speech.”

The New York Times editorial board disagreed. “His behavior was cowardly as well as irresponsible, manipulating students, jeopardizing their safety and damaging their future careers,” the Times editorial said. “It makes pawns of vulnerable young men and women, while the professor as instigator seeks immunity behind the shield of tenure.”

Dr. Franklin later sued Stanford, seeking back pay and restitution, but California courts upheld the university’s decision.

For three years, he was blacklisted — denied employment by “hundreds of colleges,” as he wrote in a memoir, “Crash Course: From the Good War to the Forever War,” published in 2018.

He was finally hired in 1975 by Rutgers University-Newark, where a decade later he was named the John Cotton Dana Professor of English and American Studies. He remained at Rutgers until his retirement in 2016, publishing on a wide range of topics.

Vietnam was a recurring theme. In 1992, in “MIA: Or Mythmaking in America,” Dr. Franklin examined the widespread and false belief that American soldiers were still being held captive in Indochina. It was a myth, he argued, created by Hollywood, in movies like “Rambo: First Blood Part II” and by the Reagan administration, to prevent normalization of relations with communist Vietnam.

“Still reluctant to understand the origins and terrible legacy of the Vietnam War, many Americans console themselves with legends,” wrote Todd Gitlin of Dr. Franklin in The Times Book Review. “One reads his account and wonders what was really missing from the action in Vietnam.”

Dr. Franklin had a lifelong interest in science fiction and examined how its supposed pulp themes were at the core of American culture. He wrote a book about the work of Robert A. Heinlein and another about how mainstream 19th-century writers like Poe and Hawthorne tackled science fiction. In 1992, he was guest curator of an exhibit devoted to “Star Trek” at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum.

Long after he became active in radical politics, he became a saltwater fisherman off the New Jersey coast. His interest developed into a book on Menhaden, a key fish in the coastal food chain, The Most Important Fish in the Sea (2007).

The book raised awareness of the commercial overfishing of menhaden for fertilizer and animal feed, which led the Atlantic Marine Fisheries Commission in 2012 to impose the first catch limits. The limits have been credited with encouraging the recovery of menhaden along the Atlantic coast and the return of whales, which feed on the fish, to New York Harbor.

Howard Bruce Franklin was born on February 28, 1934 in Brooklyn, the only child of Robert Franklin, who held low-paying jobs on Wall Street, and Florence (Cohen) Franklin, who worked as a fashion illustrator for newspaper advertisements.

Bruce, as he was known, became the first in his family to attend college when he won a scholarship to Amherst. There he felt alienated from his largely privileged fellow students. “I despised them from the tops of their crew cuts to the soles of their white dollars, hating mostly the smug swagger in between,” he once told a group of college professors.

After graduating with honors in 1955, he worked as a mate on tugboats in New York Harbor. In 1956 he married Jane Ferrebee Morgan, who had grown up on a tobacco farm in North Carolina and worked in the United Nations intelligence department.

Dr. Franklin served three years in the Air Force as a navigator and squadron intelligence officer in the Strategic Air Command.

He was accepted into the Ph.D. He studied English at Stanford, received his BA in 1961, and was hired as an assistant professor of English and American literature. His first book, The Wake of the Gods: Melville’s Mythology, was published in 1963 and remained in print for decades.

At the time, he considered himself a conventional democrat. He was a volunteer on Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 presidential campaign.

But America’s growing involvement in Vietnam changed all that. In 1966, Dr. Franklin helped lead an unsuccessful campaign, which gained national attention, to shut down a napalm plant in San Francisco Bay.

He identified as a revolutionary, a word he defined, according to Time magazine, as “someone who believes that the rich who run the country should be overthrown and that the poor and working people should rule the country.” In 1972, the year he was fired from Stanford, he published The Essential Stalin: Major Theoretical Writings, 1905-1952.

In an interview that month with The Times, Dr Franklin denied hiding Mr Beattie but praised the violence that led to his escape.

“We believe that most people in prison should not be there, that robbing a bank is not a crime and neither is drug use,” he said. “And we believe that those in prison should be freed by all means.”

Several members of Venceremos were convicted of murder, but the charges against Dr. Franklin were dropped.

“My father was able to prove that he was not where Ronald Beatty said he was,” said his daughter Karen.

In addition to Mrs. Franklin, a forensic psychologist, Dr. Franklin has another daughter, Gretchen Franklin, a criminal defense attorney. a son, Robert, a physician; and six grandchildren. His wife, who wrote books on Cuban-US relations and gave educational tours to Cuba, died in 2023 after 67 years of marriage.

Karen Franklin said she never asked her father if he regretted his rhetoric about violently toppling the government. “I don’t think he thought of himself as a Maoist or a Stalinist anymore,” he said. “He was part of a movement that was national and international in the 60s and 70s. He was a leader in this movement. he was also drawn into this movement, and when the movement was over his politics softened.’