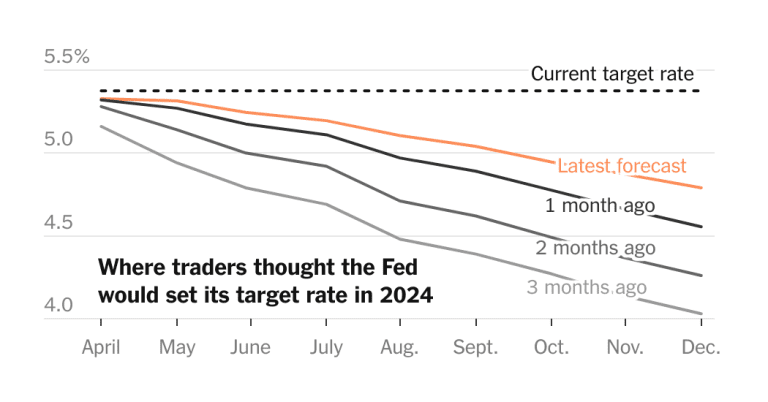

Investors were betting on Federal Reserve rate cuts as early as 2024, betting that central bankers would cut rates to around 4 percent by the end of the year. But after months of persistent inflation and strong economic growth, the outlook is starting to look much less dramatic.

Market pricing now suggests that rates will end the year in the neighborhood of 4.75%. That would mean Fed officials had cut interest rates two or three times from today’s 5.3 percent.

Policymakers are trying to strike a delicate balance as they consider how to respond to the economic moment. Central bankers don’t want to risk hurting the labor market and causing a recession by keeping interest rates too high for too long. But they also want to avoid cutting borrowing costs too soon or too much, which could prompt the economy to accelerate again and inflation to take root even more firmly. So far, officials have maintained their forecast for rate cuts in 2024, while making clear they are in no rush to cut them.

See what policymakers are considering as they consider what to do with interest rates, how incoming data could reshape the path they take, and what it will mean for markets and the economy.

What does “higher for longer” mean?

When people say they expect rates to be “high for longer,” they often mean one or both of two things. Sometimes, the phrase refers to the short term: The Fed may need more time to start cutting borrowing costs and move on to those reductions later this year. At other times, it means interest rates will remain significantly higher in the coming years than was normal in the decade before the 2020 pandemic.

Looking ahead to 2024, top Fed officials have been very clear that their primary focus is on what happens to inflation as they discuss when to cut rates. If policymakers believe that price increases are going to return to the 2% target, they could feel comfortable cutting even in a strong economy.

In the longer term, Fed officials are likely to be more influenced by factors such as labor force growth and productivity. If the economy has more momentum than in the past, perhaps because government investment in infrastructure and new technologies like artificial intelligence are spurring growth at a higher rate, perhaps interest rates need to stay a bit higher to keep the economy in even keel operation.

In an economy with steady vigor, the low interest rates of the 2010s may turn out to be too low. To use the economics term, the “neutral” factor setting that neither heats nor cools the economy may be higher than it was before Covid.

For 2024, sticky inflation is the concern.

Some Fed officials recently argued that interest rates could remain higher this year than the central bank’s forecasts suggested.

Policymakers predicted in March that they were still likely to cut borrowing costs three times by 2024. But Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, suggested during a virtual event last week that he could envision a scenario in which the Fed did not lower interest rates at all this year. And Raphael Bostic, the president of the Atlanta Fed, said he did not foresee a rate cut until November or December.

The caution comes after inflation – which has fallen steadily throughout 2023 – has moved sideways in recent months. And with new pressures surfacing, including a rebound in gas prices, mild pressure on supply chains after the Baltimore bridge collapse and home price pressures taking longer than expected to fade from official data, there is risk of continued stagnation.

However, many economists believe it is too early to worry about stagnating inflation. Although price increases were faster in January and February than many economists had expected, that could be partly due to seasonal quirks and came after significant progress.

The Consumer Price Index inflation measure, due on Wednesday, is expected to ease to 3.7% in March after stripping out volatile food and fuel costs. That’s down from an annual reading of 3.8 percent in February and well below a peak of 9.1 percent in 2022.

“Our view is that inflation is not sticking,” said Laura Rosner-Warburton, senior economist at MacroPolicy Perspectives. “Some areas are sticky, but I think they’re isolated.”

The latest inflation data does not “materially change the overall picture,” Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chairman, said during a speech last week, even as he indicated the Fed would be patient before cutting rates.

The focus is also on the longest duration.

Some economists — and, increasingly, investors — believe interest rates could remain higher in the coming years than Fed officials have predicted. Central bankers forecast in March that interest rates would fall to 3.1% by the end of 2026 and to 2.6% over the longer term.

William Dudley, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, is among those who believe interest rates could stay higher. He noted that the economy expanded quickly despite high interest rates, suggesting it can handle higher borrowing costs.

“If monetary policy is as tight as President Powell claims, then why is the economy still growing at a rapid pace?” said Mr. Dudley.

And Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, wrote in a shareholder letter this week that major societal changes — including the green transition, supply chain restructuring, rising health care costs and increased military spending in response to geopolitical tensions – could “lead to stickier inflation and higher interest rates than markets expect.”

He said the bank was prepared for “a very wide range of interest rates, from 2 percent to 8 percent or even more.”

Borrowing would be more expensive.

If the Fed does leave rates higher this year and in the years to come, it will mean that cheap mortgage rates like those that prevailed in the 2010s will not return. Likewise, credit card interest rates and other borrowing costs will likely remain higher.

As long as inflation isn’t stuck, that could be a good sign: Superlow interest rates were an emergency tool the Fed used to try to revive a battered economy. If they don’t come back because growth has more momentum, that would be evidence of a stronger economy.

But for would-be homeowners or entrepreneurs who have been waiting for borrowing costs to come down, that could offer limited comfort.

“If we’re talking about interest rates that are higher for a longer period of time than consumers expected, I think consumers would be disappointed,” said Ernie Tedeschi, a researcher at Yale Law School who recently left the White House Council of Economic Advisers. .