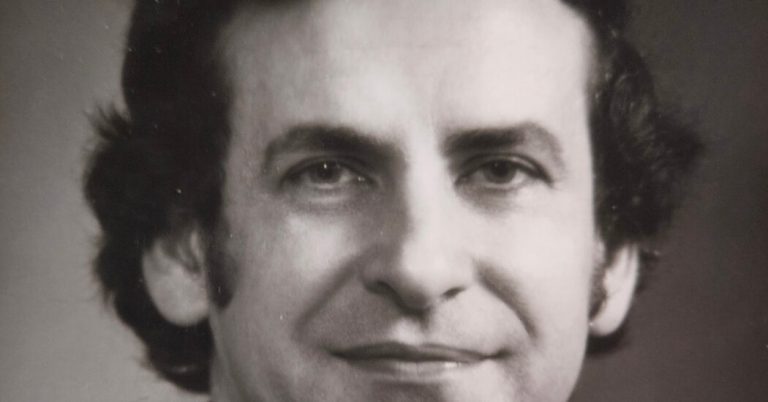

Charles Sallis, a Mississippi historian who collaborated on a textbook that revolutionized the teaching of Mississippi’s troubled history, died Feb. 5 at his home in Jackson, Miss. He was 89 years old.

His death was confirmed by his son Charles Jr.

Until the 1974 publication of ”Mississippi: Conflict & Change,” which Mr. Sallis wrote and edited with the sociologist James W. Loewen, high school students in the state had been fed a dilemma that omitted the horrors of slavery, lynching , the Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow and largely omitted the civil rights movement.

Mr. Sallis, originally from Mississippi, had grown up immersed in the conventional racism of his state. But he had long since realized that most of what he had been taught was wrong: slave owners were not benevolent, Reconstruction was not a story of Black corruption, and white supremacy was not inevitable. He and Mr. Loewen set out to change the way young people in Mississippi thought about their state.

In 1970, as the most active phase of the civil rights revolution drew to a close, Mr. Sallis, professor of history at the relatively liberal Millsaps College, along with Mr. Loewen, who then taught nearby at historically black Tougaloo College, were sitting to rethink their state’s past, along with a small group of students and faculty from both schools. Over the next four years, the group of nine produced a ninth-grade history textbook so forceful, honest, and compelling in its review of the state’s grim history that Mississippi’s textbook purchasing board banned it from use in schools almost as soon as it appeared.

Outside Mississippi – a state the historian James W. Silver had called “the Closed Society” in a landmark book in 1964 – the efforts of Mr. Sallis, Mr. Loewen and their team were immediately recognized.

Child psychiatrist Robert Coles wrote in The Virginia Quarterly Review, “Mississippi: Conflict & Change” was “insightful, lucid, and sometimes disturbing.” Duke University historian Lawrence Goodwyn, in a letter to Mr. Loewen, called it “an extraordinary achievement” and “the best history of an American state that I have ever seen.”

In 1976, the book won the Southern Regional Council’s Lillian Smith Award for best Southern nonfiction book.

But it would take five years of court battles against stubborn state officials, a trial and a federal judge’s decision in 1980 for Mississippi to accept the book into state schools.

Asked to explain himself and the book at trial by the state’s attorney, Mr. Sallis was coy. He said that he and his colleagues simply wanted to prepare a textbook that would be “an antidote or medicine to correct the racial imbalance in the traditional Mississippian texts.” In an earlier deposition, he denounced “the nation’s failure to live up to its commitment to equality” during Reconstruction.

Mr. Sallis focused on that period, his specialty, on the book. Of the blacks who briefly came to power after the Civil War, he wrote, “They were reasonable in their use of political power and in their actions toward white Mississippians. All they were asking for was equal rights before the law. All in all, Mississippi was especially fortunate to have able Black leaders during these years.”

This was a radical departure from the view Mississippian students had been fed for years with textbooks like John K. Bettersworth’s “Your Mississippi,” which suggested that Reconstruction was a time of unrelenting horror visited upon white people. “Reconstruction was a worse fight than ever,” Mr. Bettersworth wrote, imprecisely.

Mr. Sallis went on to describe, in some detail, the brutal suppression of Blacks that followed Reconstruction and the so-called Mississippi Plan of 1875, which included the violent suppression of the Black vote. White people, he said, had “unleashed a reign of terror” to regain and maintain the control they would have for the next 90 years.

It was a powerful stand for mid-1970s Mississippi and represented the end point of a personal transformation for Mr. Sallis, as Mr. Eagles’ book makes clear.

Growing up in Mississippi, Mr. Sallis was a “good-natured bigot,” Mr. Eagles says.

“In other words, I honestly believed that black people were inferior,” Mr. Sallis said.

Only after serving with Black Army officers at Fort Knox in Kentucky and reading such important books as Vernon Lane Wharton’s “The Negro in Mississippi: 1865-90” did Mr. Sallis begin to move away from the conventional Mississippian way of thinking — a change reflected in his dissertation, “The Color Line in Mississippi Politics,” which he wrote at the University of Kentucky before receiving his Ph.D. in 1967.

William Charles Sallis was born Aug. 27, 1934, in Tremont, Miss., to William Lazarus Sallis, who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Myrtle Cody Sallis. He attended Greenville High School and graduated from Mississippi State University with a degree in education in 1956, after which he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army. He received his master’s degree in 1956.

He taught history at Millsaps from 1968 to 2000.

In addition to his son Charles Jr., he is survived by his wife, Harrylyn Graves Sallis; another son, David; a daughter, Victoria; two grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

“Mississippi: Conflict & Change” is out of print, but “it paved the way for other historians to say, ‘OK, we can deal with these issues,'” said Charles Sallis Jr. “The reality of this book inspired later books.”